(#AmazonAdLink)  My book, (#AmazonAdLink) What is Hell? is now available (#AmazonAdLink) on Amazon. I am doing a series of podcast studies that focus on some of the content from the book. The studies look at the eight key terms that are often equated with hell, and about a dozen key passages that are thought to teach about hell.

My book, (#AmazonAdLink) What is Hell? is now available (#AmazonAdLink) on Amazon. I am doing a series of podcast studies that focus on some of the content from the book. The studies look at the eight key terms that are often equated with hell, and about a dozen key passages that are thought to teach about hell.

If you want to learn the truth about hell and what the Bible actually teaches about hell, make sure you get a copy of my book, (#AmazonAdLink) What is Hell?

Also, if you are part of my discipleship group, there will be an online course about hell as well.

In previous studies, we have looked at the words sheol, gehenna, abyss, tartarus, and the ‘outer darkness.’ In each case, we have seen that none of these words describe a place of everlasting torment for unbelievers in a place of burning fire.

But what about the New Testament Greek word hadēs?

In this study, we will consider the word hadēs and whether or not it refers to hell as a place of eternal suffering and torment for unbelievers.

Is Hadēs Hell?

One of Greek words that is commonly translated as “hell” in the New Testament is hadēs. But the word hadēs is the Greek equivalent to the Hebrew word sheol.

In the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (the LXX), the Hebrew word sheol is most often translated as hadēs. And since we have already seen that sheol is best translated as “grave” or “pit,” then this hints that the word hadēs should be understood in a similar fashion (cf. 1 Cor 15:55).

But hadēs is More than Just the Grave

In the days of Jesus and the apostles, Jewish teachers were rethinking the concept of the afterlife. The idea of a future resurrection was gaining prominence, and with this idea, people were beginning to speculate about what might happen to humans after they died but before resurrection.

So while most Old Testament texts which refer to sheol can be understood as only referring to a grave in which dead bodies were laid, the New Testament texts about hadēs seem to show an evolution in thinking about what happens to humans after they die.

Those who did not believe in a future resurrection (such as the Sadducees), continued to teach that after death, all people went to the grave (sheol or hadēs) and that was the end.

But those who believed in the resurrection (such as the Pharisees), began to think that there was some sort of conscious existence for the dead as they awaited the future resurrection.

For example, the apostle Peter quotes David (Psalm 16:8-11) as saying that God would not allow his body to see corruption in hadēs, but would raise Him up (Acts 2:26-27, 31). Peter used these texts to defend the idea of the resurrection, and to explain why God raised Jesus from the dead.

Therefore, those who believed in life after death also believed that people continued to exist somewhere and somehow after death while they awaited resurrection.

But they did not have a “heaven and hell” concept as many do today. Instead, people in the days of Jesus believed that all the dead went to the same place, though with different “compartments” for the righteous and the wicked (Josephus, Antiquities, 18.14).

This concept is seen in the story of the rich man and Lazarus in Luke 16:19-31. But Jesus’ use of this imagery should not be seen as an endorsement of it. Just as someone today might tell a story about meeting Peter at the Pearly Gates without believing that this is actually what will happen, so also, Jesus could tell a story about Abraham’s bosom in hadēs (Luke 16:22-23) without actually endorsing the concept.

Yet those who believed that hadēs was an actual realm in which the dead consciously existed, also believe that the dead would not exist there forever. Instead, hadēs was a “holding tank” for people while they waited for the resurrection. At some point in the future, when the resurrection occurred, hadēs would be emptied because all of the dead within it would be raised to life.

But this was not an endorsement of Universalism. Though hadēs would be emptied through the resurrection of all people, the righteous would go away to everlasting life with God, while the rest would go away to everlasting death with the devil (cf. Revelation 20:13-14).

This idea does not match the modern concept of hell, for in this first-century way of thinking, the people who go to hadēs do not stay there forever.

So what is the New Testament concept of hadēs?

What did Jesus and the apostles have in mind when they taught and wrote about hadēs?

Several New Testament texts provide a shocking insight into the nature and location of hadēs.

Matthew 11:23 (Luke 10:15) and hadēs

For example, Jesus indicates that the hadēs is set in contrast to heaven. In Matthew 11:23, Jesus says that while Capernaum was exalted to heaven, it will be brought down to hadēs (cf. Luke 10:15). Does this mean that citizen of Capernaum were all headed for eternal suffering in the pit of hell? No, it cannot mean this, unless the citizens of Capernaum were all previously in heaven. Such an idea makes no theological sense. Even those who believe that it is possible for a person to lose their eternal life do not think that those in heaven can still be sent to hell.

Therefore, it is better to see that Jesus is speaking of both heaven and hadēs in symbolic ways.

In Matthew 11:23 and Luke 10:15, Jesus is speaking of heaven as a reference to the apparent blessing of God upon a city in this life and on this world. The city of Capernaum had great fame, honor, glory, wealth, power, and respect in the minds of most people.

Going down to hadēs, therefore, symbolizes the opposite. The city would lose its power, privilege, and position and would become weak, poor, and desolate, much like Tyre and Sidon (Luke 10:13) or Sodom and Gomorrah (Matt 11:23-24).

The “day of judgment” to which Jesus refers in these texts does not refer to some future judgment when all the people of these cities are condemned to eternal punishment in hell, but rather to the historical events which cause the physical destruction of the cities.

So when Jesus teaches about hadēs in Matthew 11:23 and Luke 10:15, He is speaking about the destruction of cities on this earth in history; not about the torment of human souls in fiery flames for all eternity.

Matthew 16:18 and hadēs

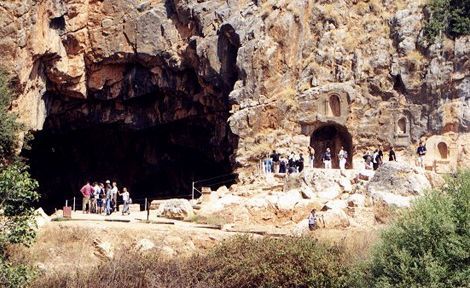

The greatest insight into what Jesus believed about hadēs is found in Matthew 16:18. In the preceding context, Peter has just declared that Jesus is the Christ, the Messiah.

In response, Jesus states that it is on this declaration from Peter that He will build His church. Jesus then says that the “gates of hadēs” will not prevail against the church. Since the church Jesus is building exists here and now, on this earth, in and through our lives, this means that hadēs also is here and now, on this earth, and it is set against the church.

Furthermore, the church is on the offensive against the gates of hadēs, rather than the other way around. But the gates will not prevail, or stand, against the attacks of the church.

When many people read Matthew 16:18, they imagine that the church exists behind a gleaming white wall, and that hell is on the outside, trying to batter down the gates.

But as I point out in my book, (#AmazonAdLink) The Death and Resurrection of the Church, the imagery is actually the opposite.

In Matthew 16:18, Jesus says that the “gates of hadēs will not prevail” against the church. In other words, it is hadēs that is behind a wall, and the church is attacking the gates.

And in order for the church to attack these gates, they must exist in this life and on this earth.

This further means that humans are imprisoned by these gates, so that the way Jesus builds His church is by attacking the gates of hadēs to rescue and deliver those within.

It appears, therefore, that in the mind of Jesus, hadēs is not a dwelling place for evil people in the afterlife, but is the experience of many people in this life, which is characterized by everything that is opposed to the ways of Jesus Christ and the will of God on earth.

So rather than life, light, liberty, and love, those who are trapped behind the gates of hadēs live in bondage, corruption, despair, and destruction.

Jesus leads His church to help free these people from their hellish life.

Hadēs is here and now, and Jesus leads to the church to set free those who trapped behind its bars.

The Book of Revelation and hadēs

The book of Revelation also contains several references to hadēs and while many people are most familiar with the reference in Revelation 20:13-14 where hadēs is emptied and its inhabitants are cast into the Lake of Fire, we must first understand the previous references to hadēs in Revelation (Rev 1:18; 6:8) before we can understand what John is talking about in Revelation 20.

In Revelation 1:18, we read that through His death and resurrection, Jesus gained the keys to death and hadēs.

What is interesting about this is that the Greek god Hadēs was occasionally depicted in Greek mythology as carrying a key to the gates of the underworld. He kept the gates forever locked so that nobody who was within could ever escape.

What is interesting about this is that the Greek god Hadēs was occasionally depicted in Greek mythology as carrying a key to the gates of the underworld. He kept the gates forever locked so that nobody who was within could ever escape.

But in Revelation 1:18, we see that Jesus now carries the keys, and He plans to throw the gates of hadēs wide open.

When Revelation 1:18 is read in connection with Matthew 16:18, we discover that when Jesus storms the gates of hadēs with the church, there is no battle waged.

Jesus simply walks up to the gates and unlocks the door, calling those who are within to “Come forth!” The task of the church is to show people how to be free and live life.

Death and hadēs are once again paired together in Revelation 6:8. Death is depicted as riding a pale horse, though the “greenish-yellow” color of a corpse is probably a better translation for the Greek word used here.

Of the four horsemen in the context, this fourth rider is the only one who is given a name (i.e., “Death”), and is also the only one who does not have a tool or weapon. However, in place of a weapon, Death has hadēs. This means that while the other horsemen accomplish their devastation through an instrument, death accomplishes its task through hadēs.

In other words, hadēs is not a place to which people go after they die; instead, hadēs is the tool by which the rider on the pale horse brings death and destruction upon the world.

Death comes upon this world through the instrument of death, namely, hadēs.

Once again, this shows that hadēs is a present experience for some people; not a future place of existence.

In Revelation 20:13-14, we read that death and hadēs are thrown into the Lake of Fire. If we believe that hadēs is a place, then this description make little sense.

But when we recognize that death and hadēs are the powers that destroy and devastate life on this earth, then it comes as no surprise than before Jesus restores all things to the way God wants and desires them to be, He does away with death and destruction (hadēs) by throwing them into the Lake of Fire.

So “hell” is not a good translation for the Greek word hadēs

While the most basic meaning for hadēs is similar to sheol, the grave, further development in the New Testament era reveals that hadēs can primarily be understood as the power of despair, decay, and destruction that enslaves human beings in this life.

Hadēs operates in direct contradiction to the kingdom of God and the power of life, light, and love that accomplishes the will of God on earth.

Hadēs is not a place of burning suffering for the unregenerate dead. It is instead a destructive presence here on earth that ruins what God wants for our lives. And in the end, just as with everything else that is arrayed against God, hadēs will be cast into the Lake of Fire. But what does this mean?

We will discuss the Lake of Fire next week, so make sure you join us …

Conclusion

This brief study has shown that the word hadēs does not refer to hell as a place of eternal suffering in burning flames for the unbelieving dead.

So far in our study, we have seen the same thing about sheol, gehenna, the abyss, tartarus, and the outer darkness.

But what about “the Lake of Fire”? Surely this term in Scripture refers to a place of everlasting burning and torment for unbelievers! Doesn’t it? Join us next week to find out…

Do you have more questions about hell? Are you afraid of going to hell? Do want to know what the Bible teaches about hell? Take my course "What is Hell?" to learn the truth about hell and how to avoid hell.

This course costs $297, but when you join the Discipleship group, you can to take the entire course for free.

Do you have more questions about hell? Are you afraid of going to hell? Do want to know what the Bible teaches about hell? Take my course "What is Hell?" to learn the truth about hell and how to avoid hell.

This course costs $297, but when you join the Discipleship group, you can to take the entire course for free.

What gets thrown into the lake of fire then?

According to Revelation 20:13-14, death and hades get thrown into the Lake of Fire. Some people do to. But the real question is, “What IS the lake of fire?”

I’ll discuss this next week on the Podcast …

Two questions if I may

1. What’s the exegesis behind Jesus not endorsing Hades in Luke 16?

2. What becomes of people when they die?

Both questions will be answered in great detail in future podcasts. The explanations are too long to answer in a Facebook comment.

Yea, this kind of thing requires a blog post. Looking forward to it (y)

I’ve done a study of every place (as far as I know) in ancient and classical literature of where Hades is used (extra-biblical. LXX, the Bible). This word does refer to the afterlife and not this life. It is the ‘unseen (a=not des (eido/seen) underworld, the afterlife.

Hi Bill,

Hades is the greek for the word-concept of old testament Sheol.

If you are a protestant, you probably do not accept 2 Maccabeus. But you can ask any Jewish friend and they will tell you that in Biblical times and up to this day for 12 months jews pray the Qaddish or Kaddish for their dead.

Now, if one is in Heaven, they need no prayer, if they are in Hell, then there’s no use praying for them. So why pray?

There must be an intermediary state. That place-state is Hades, Sheol in Hebrew, or Purgatorium in Latin.

Since “Nothing unclean can enter Heaven (Rev. 21,27), Hades is a place where the saved souls remain for a period of time for final purification before they can be admitted into heaven.

Hellen

I’m not Jewish so I’m certainly not an expert on the subject, but my understanding is that the Kaddish is focused on praising God’s goodness despite the death of loved ones, and is not in any way praying for the salvation of their departed souls.

“Since “Nothing unclean can enter Heaven (Rev. 21,27), Hades is a place where the saved souls remain for a period of time for final purification before they can be admitted into heaven.”

^^I’m not saying you are incorrect about this, but in Luke 16:23 the rich man is in torment in Hades. It seems very unlikely that saved souls would be in the same place of torment as unsaved souls? Just pointing that out. I’m still trying to understand this whole dynamic…

Hi Jesse,

I think your understanding of the Kaddish (or Qaddish) is not 100% accurate. Those prayers are indeed the offered up to God but as a petition on behalf of the deceased. They believe that unless a Jewish person observed diligently all the precepts of the Law during their lifetime, as well as their Mitzvahs performed in life out-weighted their sins upon death, the deceased will most definitely spend sometime purifying his souls. Usually, they pray for about 11 months, since praying for a whole year would come across as an insult to the dead.

Regarding your comment on Hades, I think there is a little confusion. The dammed soul go to hell, not to Sheol or Hades. That place of eternal damnation , in Judaism, is called Gehenna.

Hi Hellen,

Thanks for the clarification. I will defer to you on the subject of the Kaddish because my knowledge of it is rather limited.

I apologize, I believe I misunderstood the point of your comment. I do indeed understand the distinction between Sheol/Hades and Gehenna. I am aware of what Gehenna was and it’s significance and meaning in Jewish religion/culture/history.

I’m curious though – what is your belief or understanding of Gehenna and it’s usage in the New Testament? Do you hold the view that Gehenna is a place of eternal punishment for those that ultimately reject Christ (the “traditional” Biblical view of hell)?

I hope my comment doesn’t come off as judgmental or like I’m baiting you. I am geniunely curious of your opinion. I’m delving into things that I haven’t given much thought to in my whole life up until recently. Thanks in Advance.

Hi Jesse, no need to apologize, and no, your comment did not offend me.

Well, I am not an expert, but my understanding of Gehenna is that it is a place of eternal punishment, similar to the Christian understanding of Hell. While Sheol is more a transient place where the souls remain until they are finally admitted into Heaven… But, as said, I am not an expert.

Hades was understood to be the place where both the righteous and unrighteous would go. There were different compartments based on the righteousness of the person (Tartarus, the asphodel fields, and more). Hell is based on the sister of Loki (Hel). A Nordic goddess and also referred to her realm. Hades referred to the Greek ‘god’ and his realm. The Nordic/early Anglo word ‘Hel’ was a close fit for Hades and thus was translated for it. So it is a fine translation. Countless passages refer to Hades as a place where the dead (and sometimes the living) would go to. One could also leave this place by going up and out of it once righteousness was obtained.

. Ovid Metamorphoses book 10 card 1: “Her last word spoken was ‘Farewell!’ which he could barely hear, and with no further sound she fell she fell from him again to Hades.-Struck quite senseless by this double death of his dear wife…all things are due to you…we must go to one abode’. ‘They shot him down with their arrows. And he is punished even after death; for vultures eat his heart in Hades/κολαζεται δε και μετα θανατον’ (Apollodorus, Library and Epitome 1.4.1). In Euripides’s Alcestis card 121 line 125 he refers to Hades as “the dark place” and in the same book he refers to a dying mother saying goodbye to her children as she knows that death is coming and that “πλεσιον αιδας” Hades is near. The above are a few examples among many of how it refers to the afterlife. It wasn’t only a place of kolasis but also a place for the righteous.

Ovid Metamorphoses book 10 card 1 uses the phrase “the gloom of Tarturus”. The passage refers to it being a part of Hades. “the lower world, Hades; especially that portion which was set apart for the wicked http://logeion.uchicago.edu/index.html#Tartarus ‘ But them Sky bound and cast into Tartarus, a gloomy place in Hades as far distant from earth as earth is distant from the sky/ὁ δὲ τούτους μὲν τῷ Ταρτάρῳ πάλιν δήσας καθεῖρξε, τὴν δὲ ἀδελφὴν Ῥέαν γήμας, ἐπειδὴ Γῆ…’ Apollodorus

You can go to this link and see very many examples of where ‘Hades’ clearly refers to a place that is not on this earth but rather the afterlife/underworld/realm of ‘hades’. The NT usage of the word is similar to the ancient Greek. It was a place where all (precross) would go after death (with varying levels of pleasure (such as for Abraham) or pain (like the rich man) or something in between. If you could provide evidence that the NT or others during the 1st century gave a new meaning to this word that was quite different than the previous centuries, I’d love to see that. http://artflsrv02.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/perseus/showrest_?conc.6.1.1497.0.99.GreekApr19

Why would Jesus use ancient Greek world view at all? (Jews did not believe in after-life in some hidden “underworld” UNTIL they were influenced by pagans’ belief systems.) http://askelm.com/doctrine/d030602.htm

I discuss many of those texts in my forthcoming book, which I would say provide evidence in themselves that hell is not really a place.

Redeeming God with Jeremy Myers Such as some usages with very different meanings in the 1st century than from the classical period? Or mainly using the Bible to deduce the meaning and interpreting it non-traditionally? That could be a valid argument. Surely though the quotes I listed in these comments here cannot be understood to say that ‘Hades/Tartarus’ was not considered a place. You would agree with that right? What about the quotes from Classical Greek that I listed here? They seem like they must refer to it as a place (plus I could give a plethora of other quotes). I’d be interested to see what evidence there is for such a drastic change in the meaning of these words.

Jesus never mentioned Hell once.

Yes He did, and He did so numerous times (Matthew 5:29-30, 10:28; Luke 16:19-30).

Why does the bible use the term hades. I need a priest.

Is there another chance to repent in Hades before the Great White Throne Judgement?

Revelation 20:10

and the devil who had deceived them was thrown into the lake of fire and sulfur where the beast and the false prophet were, and THEY WILL BE TORMENTED DAY AND NIGHT FOREVER AND EVER.

(Do you “Spiritalize” this verse or do you understand it LITERALLY)?

So Jesus refers to Greek mythology being Hebrew the God of Israel based His covenant on Greek teachings, how can we escape so great a salvation, frustration after frustration to those that can’t except this teaching what a repetitive thing to live, what the weeping and nashing of teeth about then they get off with a slap on the wrist those that keep crusifyig the Son of God, lake of fire I guess I wouldn’t mind living in frustration for all eternity I’ve had my fun in this life it would be like regular prison, this is no wrath of God like in the day of Noah