Back in 1995 I was a 5-point hyper Calvinist. Over the course of the next 3 years, and through studying various passages and reading various books, I dropped belief in the third point of Calvinism: Limited Atonement. But I told myself that I would never drop the other 4 points.

Back in 1995 I was a 5-point hyper Calvinist. Over the course of the next 3 years, and through studying various passages and reading various books, I dropped belief in the third point of Calvinism: Limited Atonement. But I told myself that I would never drop the other 4 points.

At that time, I read some book by Clark Pinnock (I don’t remember the title) which recounted his exodus from Calvinism. He said that he too began by dropping Limited Atonement, and over the next several years, the other four points dropped out of his theology as well. He then went on to become a defender of inclusivism and open theism.

After reading that book, I wrote a paper called “The Pinnockio Path” in which I slammed Clark Pinnock for his theological conclusions. I basically called him a lying (Pinocchio … get it?) heretic. In the paper I said that while Pinnock had rightly dropped the third point of Calvinism, he should have stopped there (like me), for the rest of his theological journey led him into some strange lands and heretical conclusions.

Looking back now, I laugh at myself, for it appears I have traveled nearly the same road as Clark Pinnock. I don’t defend inclusivism or open theism (Yet???), but I no longer consider myself a Calvinist of any shape or size. (I call myself a 2 and 1/2 point Calvinist, because I believe in half of each point: depravity, election, atonement, grace, and the saints).

I have also learned, I hope, to be a little more gracious toward those who have studied longer and traveled further than I have, knowing that I might end up exactly where they are, if I keep studying and following where Jesus leads (to the best of my ability).

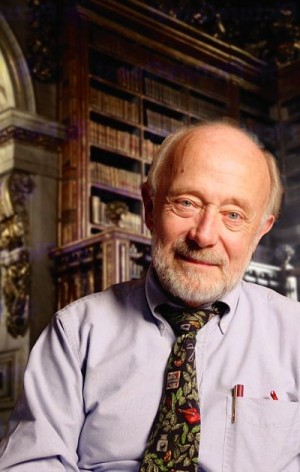

All this is an introduction to a book I just finished reading, titled Convictions, by Marcus Borg. It is sort of a theological autobiography, in which Borg recounts his theological journey into what he calls “Progressive” Christianity, and explains the central ideas and convictions (hence the name of the book) which led him to the central beliefs he now holds.

As I read, I found that strange sense of déjà vu from when I read Clark Pinnock so many years ago. I recognized that much of the early questions and studies that led Borg to where he now finds himself, are the same questions and studies that I am currently facing. Does that mean that just as I followed the “Pinnockio Path” I am now on the Path of the Borg so that “resistance is futile”? (You Star Trek fans will get that.)

It could be. And if so, I accept it, because as I look at Borg’s convictions, I find myself almost there already.

Among his convictions which Marcus Borg explains in his book is the idea that salvation is about way more than just going to heaven when we die. As I have argued for years, the Gospel is about all of life, not just what happens to us after death. Salvation is not just about how we will live in the hereafter, but also how we live in the here and now.

Among his convictions which Marcus Borg explains in his book is the idea that salvation is about way more than just going to heaven when we die. As I have argued for years, the Gospel is about all of life, not just what happens to us after death. Salvation is not just about how we will live in the hereafter, but also how we live in the here and now.

Another conviction Borg unfolds is the idea that Jesus is the lens by which we must read an interpret all of Scripture. This too is something I have been writing about for two years or more, and am always thrilled when I encounter other writers and scholars saying the same thing.

Then he has a chapter on how the Penal Substitutionary view of the atonement leads to some bad theology about God and our sin. Borg argues that the cross still matters and is central to Christianity, but the cross was not some sort of blood sacrifice as a payment for sin or a strange way of God dealing with His own anger by killing His Son.

There are other chapters as well, all of them good. There was an excellent chapter on Borg’s conviction about peace and non-violence.

The chapter that challenged me most was the chapter about how the Bible is true even though it isn’t literally true. I am really grappling with the doctrines of inspiration and inerrancy right now, and found much of what Borg said to be helpful as he explained how he reads and understand the Bible, even though he doesn’t believe the Bible is inerrant.

This is a great introduction to some of the central beliefs of Borg, and also to many of the central convictions of an ever-widening swath of Christians in the world today.

My only real complaint is that there were not more footnotes in the book. Since I would love to read up more on some of the ideas he presents, I would have liked to see more footnotes about where I can turn to study further, or at least a “Recommended Reading” list in the back.

Whether you agree with where Christianity is headed, or are fighting to hold back the tide, this book provides a good introduction to some of the convictions of progressive Christianity, and will both affirm and challenge many of your own theological convictions. I highly recommend it. You can get a copy of Convictions from Amazon.