Various accounts of the Egyptian Book of the Dead state that Horus was a god before he became a man, and that when he was born of the virgin Isis on December 25 in a cave, his birth was announced by a star in the East to three wise men, after which he was carried to Egypt to escape the wrath of the local king.

Various accounts of the Egyptian Book of the Dead state that Horus was a god before he became a man, and that when he was born of the virgin Isis on December 25 in a cave, his birth was announced by a star in the East to three wise men, after which he was carried to Egypt to escape the wrath of the local king.

When he was thirty, Horus was baptized by Anup the Baptizer before gathering twelve disciples and traveling around the countryside teaching and performing miracles like feeding bread to a multitude and walking on water. Finally, he was crucified, buried in a tomb, and later resurrected from the dead.

All of this was written many thousands of years before Jesus ever lived and died. I’ve written about all of this previously, showing that even if these parallels are true, they do not disprove the historical reliability of the Gospels.

But there is more.

Parallel stories in ancient myths do not mean that the Gospel accounts of Jesus are false. It may be just the contrary, that God purposefully chose some of the greatest dreams and desires of all mankind, and in Jesus, made them reality.

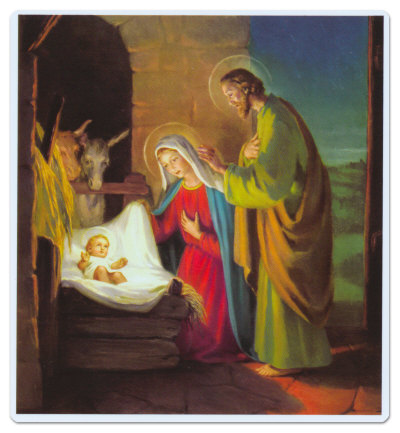

This may be one of the greatest truths of the incarnation. It is not just that God became flesh, but that God put into Jesus all of mankind’s greatest dreams and desires. To keep it “orthodox” we might say that even those dreams and desires came from God.

But is such an idea so strange? Can we not imaging that God, both in looking over history through foreknowledge and in creating humankind, put into Jesus the same sort of hopes, dreams, tales and ideas that would fascinate and hold captive the thoughts and hearts of men? Why could it not be so?

When people look for the manifestation of God, they need look no further than their own heart and mind. This is not to say that we are all god. But it would not be wrong to argue that in many ways, we are all God’s. Movies, music, and art all point to the grandeur and majesty of God, even if they first point to the creativity of men. Fiction becomes reality and dreams come to life when the invisible God makes Himself known.

It is as G. K. Chesterton wrote in The Everlasting Man:

The populace have been wrong in many things; but they have not been wrong in believing that holy things could have a habitation and that divinity need not disdain the limits of time and space.

I love Christmas carols. I really do. I have many fond memories of singing carols in church while I was growing up, and listening to them in the house during the Christmas season.

I love Christmas carols. I really do. I have many fond memories of singing carols in church while I was growing up, and listening to them in the house during the Christmas season. Silent Night is another good example of a Christmas carol that present Jesus poorly. In talking about Jesus, it contains the words, “…radiant beams from thy holy face…”

Silent Night is another good example of a Christmas carol that present Jesus poorly. In talking about Jesus, it contains the words, “…radiant beams from thy holy face…”