For many, Romans 8:28-30 presents the strongest case in the entire Bible for the Calvinistic doctrine of Unconditional Election.

This text contains what many refer to as “the golden chain of salvation,” linking God’s foreknowledge from eternity past to the glorification of Christians in eternity future. It seems that if those whom God foreknew from eternity past are the same ones He brings to glorification in eternity future, then sovereign Unconditional Election is the only way God could bring this about.

Here is what Paul writes:

And we know that all things work together for good to those who love God, to those who are the called according to His purpose. For whom He foreknew, He also predestined to be conformed to the image of His Son, that He might be the firstborn among many brethren. Moreover whom He predestined, these He also called; whom He called, these He also justified; and whom He justified, these He also glorified (Romans 8:28-30).

As can be seen, this text seems to strongly support the doctrine of Unconditional Election.

Calvinists on Romans 8:28-30

John Piper calls it “the most important text of all in relation to the teaching of Unconditional Election” (Piper, 5 Points, 58). Romans 8:29 begins by linking God’s divine foreknowledge with God’s predestination, and Romans 8:30 carries this predestination through calling, justification, and glorification.

It appears that Paul presents a “golden chain of salvation” from eternity past to eternity future, just as Palmer states:

What Paul is saying in Romans 8 is that there is a golden chain of salvation that begins with the eternal, electing love of God and goes on in unbreakable links through foreordination, effectual calling, justification, to final glorification in heaven (Palmer, Five Points of Calvinism, 32).

With just a cursory reading of Romans 9:29-30, it appears that Palmer is correct. It seems that Paul is saying that from eternity past, God had in mind a certain group of people whom He predestined to receive eternal life.

This group of people was called by God, justified by God, and glorified by God. Many note that even the word “glorified” is in the past tense, which seems to indicate that even when glorification is in our future, it is nevertheless settled and complete in the mind of God.

If our glorification and justification was settled in the mind of God through His calling and predestination from eternity past, then this text seems to irrefutably support Unconditional Election.

The Problem with the Ordo Salutis Romans 8:28-30

However, when Romans 8:28-30 is understood in context, not only does it fail to support Unconditional Election, but this text actually refutes it.

In some theological circles, there is an ongoing debate over something called ordo salutis, or “the order of salvation” (Sproul, Grace Unknown, 144).

The debate is basically about the logical order of events and decisions in God’s plan of salvation.

For example, while everybody agrees that justification precedes glorification, there is much debate about whether God’s decree to redeem humanity preceded or followed the human fall into sin. The option you choose leads to numerous ramifications about your understanding of God’s sovereignty, human freedom, and what (or who) initiated God’s plan of redemption.

One of the other issues in the debate over ordo salutis is in regard to God’s foreknowledge and predestination.

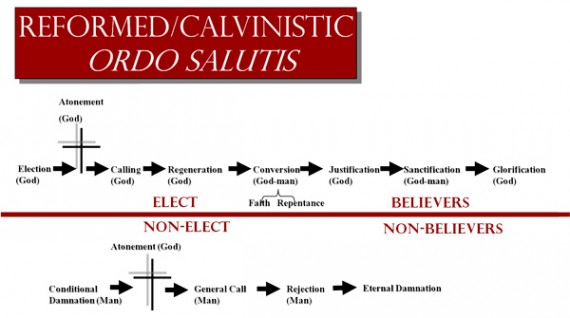

The Calvinistic Ordo Salutis looks like this:

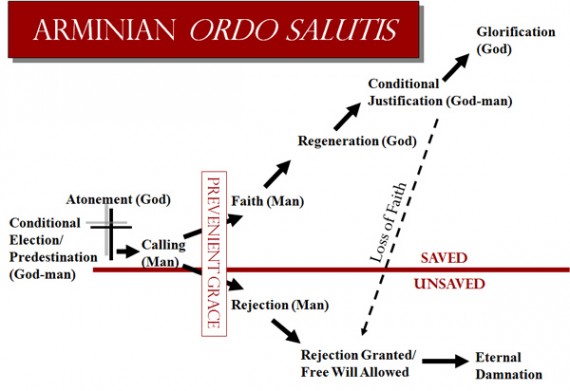

Arminians, with their desire to maintain human free will, often say that God, in eternity past, looked down through time to see who would choose Him out of their own free will, and then it is these whom God predestined for eternal life. In this order of events, God’s foreknowledge logically precedes God’s predestination. Calvinists disagree, and say that such an order of events makes God dependent upon human choice. They argue instead that God knows what will happen in the future because He predestined, or foreordained, all that will happen (Demarest, The Cross and Salvation, 36-44; Piper, 5 Points, 59-60).

Yet when Paul talks about the “order of salvation” in Romans 8:28-30, he does not follow the normal Calvinistic order. Instead, he follows the Arminian order. He puts foreknowledge before predestination.

In an attempt to explain this, Edwin Palmer explains that foreknowledge carries the idea of having a loving relationship with someone:

The word translated by the older versions as “foreknew” is a Hebrew and Greek idiom meaning “love beforehand.” … Paul is using the Biblical idiom of “know” for “love,” and he means “whom God loved beforehand, he foreordained” (Palmer, Five Points of Calvinism, 31-32; cf. Boettner, Predestination, 100).

The idea that God’s foreknowledge is best understood as God’s eternal love is correct, but this still doesn’t solve Palmer’s dilemma, that Paul places God’s foreknowledge prior to God’s predestination. Even with Palmer’s exegetical sleight-of-hand in substituting in new terminology for Paul’s words, he still cannot get around the fact that Paul has God’s foreknowledge (or eternal love) preceding God’s foreordination (or predestination).

A. W. Pink attempts similar gymnastics when he uses the word “for” at the beginning of Romans 8:29 to say that the phrase “whom He foreknew” points back to part of the last clause of Romans 8:28, “to those who are called” (Pink, Sovereignty of God, 172).

In this way, Pink is able to base God’s foreknowledge on the calling of God, thus maintaining some semblance of the preferred Calvinistic ordo salutis. But this just confuses things further, because then Paul re-reverses the order in Romans 8:30 by putting God’s calling after predestination. Furthermore, since Calvinists often equate God’s “effectual call” with Irresistible Grace and God’s predestination with Unconditional Election, A. W. Pink has just reversed the order of TULIP as well, by placing the “I” before the “U” (Vance, Other Side of Calvinism, 389). It gets very confusing listening to Calvinists try to explain Paul’s words.

R. C. Sproul also notes the difficulty in Romans 8:29-30, and tries to explain it away by stating this:

We notice in this text that God’s foreknowledge precedes his predestination. Those who advocate the prescient view assume that, since foreknowledge precedes predestination, foreknowledge must be the basis of predestination. Paul does not say this. He simply says that God predestined those whom he foreknew. Who else could he possibly predestine? Before God can choose anyone for anything, he must have them in mind as objects of his choice. … [So] in actuality Romans 8:29-30 militates against the prescient view of election (Sproul, Grace Unknown, 143. He later goes on to argue for the same meaning of “foreknew” as “fore loved” as Palmer uses above. See p. 145).

I am not sure if “militates” is the right word, as Sproul’s argument is much weaker than he believes. According to Sproul, Paul is simply saying that God knows whom He will choose before He chooses them.

This would be fine, except that most Calvinists argue the opposite, that God only knows whom He will choose because He first chose them.

According to the Calvinistic ordo salutis, predestination and foreordination come before foreknowledge and election. So just like Palmer, Sproul is right about what Paul seems to say, but is in disagreement with what Calvinists typically argue.

So does this mean the Arminian is right?

No.

Calvinists rightly criticize Arminians for saying that God looks down through the halls of time to see who will believe in Him for eternal life, and then He elects, chooses, or predestines those people to be the objects of His grace and love.

Calvinists say that this makes God subject to the will of human beings, and in fact, puts the whole plan of salvation at risk. I agree with what Boice and Ryken say on this point.

[Some teach] that God bases his election of an individual on foresight, foreseeing whether or not a particular individual will have faith. … [This] actually means that men and women elect themselves, and God is reduced to a bystander who responds to their free choice. Logically and causally, even if not chronologically, God’s choice follows man’s choice (Boice, Doctrines of Grace, 99).

After all, what if God, in looking down through the halls of time to see who would choose Him, discovered that, much to His dismay, nobody had chosen Him? God would have been bound by this foreknowledge to do what He foresaw; otherwise His foreknowledge would have been in error.

If God only looks forward in time to see what it is that He should be doing in regard to human salvation, then God is bound by what He foresees to carry it out, even if He defeats Him and His purpose.

Right about now, you may be feeling like this discussion of Romans 8:28-30 is getting off into the weeds.

On the one hand, we have seen that while some Calvinistic explanations of various words of this text do in fact teach what those words say, we have also seen that the Arminian ordo salutis better fits the logical order in which Paul lists these words.

Yet the Arminian ordo salutis creates vast theological problems for the interplay between divine sovereignty and human freedom.

How then are we to proceed? What is Paul saying? How can we understand this text?

The solution seems to lie in the middle ground between Calvinism and Arminianism, which is discovered by letting Paul’s words speak for themselves, which we will look at tomorrow.

Until then, what are your thoughts on the ordo salutis debate? Are you familiar with it? Is it all new to you? Do you have an opinion? Do you even care?

If you want to read more about Calvinism, check out other posts in this blog series: Words of Calvinism and the Word of God.