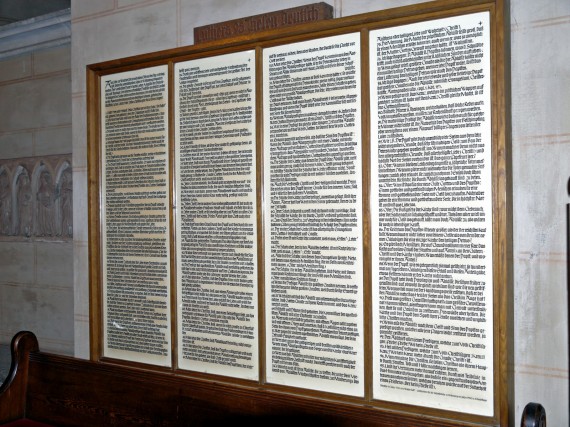

From the simplicity of the Apostles’ Creed spawned an ever-increasing number of doctrinal statements, with ever-increasing length and complexity. Some of the more well-known and famous doctrinal statements of church history include the following:

- The Nicene Creed (325 AD)

- The Second Nicene Creed (381 AD)

- The Definition of Chalcedon (451 AD)

- The Canons of Constantinople (869 AD)

- The Augsburg Confession (1530 AD)

- The First Helvitic Confession (1536 AD)

- The Council of Trent (1542-1563 AD)

- The Belgic Confession (1561 AD)

- The Thirty-Nine Article (1571 AD)

- The Canons of Dordt (1618 AD)

- The Westminster Confession of Faith (1646 AD)

- Vatican II (1962-1965 AD)

- The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy (1978 AD)

These statements and creeds are only some of the more well-known and widely accepted by large segments of Christianity. We are at the point today where there are thousands of different doctrinal statements for the thousands of different denominations, churches, and ministries. While the vast majority of these doctrinal statements were created primarily for the purpose of defining one group’s distinctive beliefs without condemning those who believe differently, nearly every statement contains points that are considered “non-negotiable” and which will cause churches to separate from others who believe differently, and even condemn these other groups as “unsaved.”

Why Have Creeds?

Ultimately, the reason behind the development of all of these statements remains the same. While on the surface, people claim that the statements are so we can know the truth, the statements ultimately come down to a desire to control and condemn others. If you disagree with this, just suggest to you pastor that the church discard its doctrinal statement and then see what he says. He will most often say something along the following lines:

We need the doctrinal statement so people know what we believe, and so we can take a stand on the truth. If we got rid of it, how would we know who could teach Sunday school, and who could lead Bible studies, and who could preach sermons? What is stopping a Mormon, or a Jehovah’s Witness, or a Universalist, or an Arminian from becoming a member and teaching their heresy to others?

People want to know who is a true Christian, and who is not. They want to be able to divide the saints from the sinners. The Orthodox from the Heretics. They want to know who is in, and who is out. Creeds and doctrinal statements help do this.

On the surface, this is commendable. Taking a stand for truth is always commendable. And I admit that those who write doctrinal statements are hoping to define and defend the truth, to protect it from all the lies and false teaching that is out there.

But there are several problems with the development of doctrinal statements as a way of protecting the truth. First, they set us up as judge instead of Jesus. Second, they end up destroying the truth and destroying people, rather than defending the truth or protecting people. And finally, they completely miss the entire point of the Gospel and the teaching of Jesus.

We will look at each of these problems in later posts, before turning to suggest a solution for how we can know and live the truth as Jesus intended. I am not against right doctrine; just against the improper use of doctrine.

Jeremy,

I know one pastor who recently just succeeded at ditching his church’s doctrinal statement entirely. I agree with some of his reasons for doing it, but it’s not clear to me that this is a good idea, and I look forward to hearing your suggestions on the subject.

What gives me pause is that standards are just inevitable. I learned this lesson in a discussion about school uniforms: someone will decide what “the well-dressed student” will look like. It may be the administration, or a small group of trendsetting children, or a large group of well-funded advertisers, but the decision will be made, through one mechanism or another, and enforced through one mechanism or another. When a school administration imposes a dress code or a uniform, they are not imposing control where there was none. They are wresting control from advertisers, children, etc. I don’t much care whether this is advisable in a particular case; I’m just commenting on the dynamics.

Likewise, doctrinal standards are inevitable. Someone will decide what may and may not be taught within your church. Someone will decide what can be said without starting a fight, and which claims are “fightin’ words.” When you gather the whole group, hash through the issues together, and write down the results that you agree on, the result is a doctrinal statement. I’m not saying it’s the only way to go, but it’s certainly better than some options. If you don’t have a written standard, you certainly will have an unwritten one, and that can be abused just as badly.

For example, I was recently un-invited to speak somewhere we both know and love because “the doctrinal distance is too great” — and this when nothing I said, or was planning to say, violated the written doctrinal statement in question. In that particular case, the real standard was unwritten, and that was that. To me this shows two things. First, a written doctrinal statement is only as good as the character of the people who are supposed to be using it. Paper doesn’t do anything; people do. If the people ignore it, it’s useless. Second, unwritten standards are at least as conducive to abusive or controlling outcomes as written ones.

Tim,

I am already softening some of my stance about doctrinal statements, and future posts will reflect this stance.

I feel in my heart what I want to say about doctrinal statements, and these posts are a weak attempt to get it out into words. Sometimes, I may overstate my case. But that is how I learn.

On an earlier comment, Sam talked about “insider theology” where a group has a hidden doctrinal statement that is not written on paper, and you don’t know what it is until after you trespass and get burned for it. You have experienced this first-hand.

And you are right. Even if the doctrinal statement is not there, controls and barriers are still set up.

So anyway, I will take a slightly different direction with this chapter in it’s final form, which I also hope will come out as I write these blog posts.

Jeremy,

No worries on the overstatement. I have such a post coming up this week, so I’m in no position to throw stones anyway, and as you say, the give-and-take that fosters is all a part of the process. I meant it when I said I’m looking forward to what you come up with — I am open to alternatives.

I liked Sam’s comment; thanks for pointing it out. I think “insider theology” is also inevitable. Nobody I know is dumb enough to claim their doctrinal statement is exhaustive, and it turns out over time that certain opinions become common currency within the group. Sam’s second example is a perfect case in point. The reading of the NT that would lead to a doctrinal statement of exclusively male eldership commonly also leads to the unwritten conviction that women should not lead or teach men. The group may not have thought it through that far at the time the statement was being written, or might have considered it so obvious as to be unnecessary to write down. But just for a thought experiment, let’s suppose that there were two different groups in the church, one that thought the above and the other that though women could teach or lead men in specific ministry contexts, but could not serve as elders over the church as a whole. Over time, this latter group diminishes as people leave or change their minds, and by the time Sam comes along, the first group is the whole church.

One could of course complain that if that’s what they all believe, they ought to update their doctrinal statement, but living people change; groups of living people change; the paperwork rarely if ever keeps up with the changes. Complaining about that is like complaining about the moon changing phase; it might be inconvenient, but it’s just a fact of life, and it couldn’t really be otherwise.

Upon reflection, my beef with the exercise of insider theology I personally encountered (above) really has more to do with it being schismatic and rulers-of-the-gentiles-esque than with the unwrittenness of it all. Again, nobody claims their doctrinal statement is exhaustive; that they hold additional beliefs dear is not really a surprise. Of course, how people handle that situation is a big test of character.

(FWIW, my big problem with the way we do doctrinal statements is not that we have them, but that we insist on 100% subscription to them. That’s idolatrous, and guarantees the only people ever in a position to revise or change it will be dishonest. I think a different subscription standard could solve a lot of problems.)

Tim,

Those are all great examples and good explanation of the issues. I am looking forward to your “over the top” post.

Hmm…one of the problems I see with doctrinal statements – and the underlying need for them – is that they often are the result of disagreements over interpretation. And many interpretational disagreements spring out of translational errors…or shifts in language and word meaning. The result is excommunication, disfellowship and condemnation to hell over things the text never actually said….sigh. But I do see the need for some guidelines. I don’t know. Maybe more personal communion with the Spirit of God would help guide better….

Katherine,

You are right on both accounts. My posts from today and the next few days will be about your first point, that doctrinal statements lead to judging others.

Future posts will argue your second point, that we still need some doctrinal statements, but for purposes other than condemning and judging others.

I hope I can make it all fit together…. At this point, I am not sure I can…

=D One never know what might be learned just in the process of trying to make things fit….

That is one reason I write! To see if I can put jumbled thoughts in my head into some sort of coherent order.

No Jeremy. The only person I want to know who is Christian is myself. I cannot know if anyone else is Christian. Only God himself knows that. So no creed means anything to me apart from scripture. In total.