Western theology has committed a terrible disservice to this imagery of a potter and clay by making it seem as if God is a deterministic puppet master up in heaven pulling the strings of people and nations down here on earth.

Western theology has committed a terrible disservice to this imagery of a potter and clay by making it seem as if God is a deterministic puppet master up in heaven pulling the strings of people and nations down here on earth.

This is exactly the opposite of what Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Paul meant by using this terminology.

The Potter and the Clay in Jeremiah 18

In Jeremiah 18, for example, while God is equated with the potter, God calls upon Israel to turn from her wicked ways and obey His voice so that they, as the pot which God is fashioning, will not be marred (cf. Jer 18:8-11).

God calls upon Israel to come into conformity to the work of His hands. If they do not, they will become marred, and He will have to reform the clay again into another vessel (Jer 18:4). He does not destroy or discard the clay; He simply forms it into another pot which will be used for a different purpose.

A similar understanding is seen in Isaiah 54 and Romans 9.

The Potter and the Clay is not teaching Determinism

There is no deterministic message in the image of the potter and the clay in Isaiah 54, Jeremiah 18, or Romans 9. If we accept the deterministic perspective of these texts, just imagine for a moment what sort of God is being portrayed. H. H. Rowley sums it up best:

Neither Jeremiah nor Paul had in mind an aimless dilettante, working in a casual and haphazard way, turning out vessels according to the chance whim of the moment … To suppose that a crazy potter, who made vessels with no other thought than that he would afterwards knock them to pieces, is the type and figure of God, is supremely dishonoring to God. The vessel of dishonor which the potter makes is still something that he wants, and that has a definite use … The instruments of wrath … were what the New Testament calls ‘vessels of dishonor,’ serving God indeed, but with no exalted service. They were not puppets in His hand, compelled to do His will without moral responsibility for their deed, but chosen because He saw that the very iniquity of their heart would lead them to the course that He could use (Rowley, Doctrine of Election, p. 40-41)

Neither Isaiah, nor Jeremiah, nor Paul had in mind a potter who purposefully created pots just so that He could smash them. No potter would do that, then or now. Instead, God is the wise potter who works with the clay to form useful tools. The vessels of “dishonor” are not vessels which are destroyed, but vessels which will be used in “ignoble” ways. They still serve important purposes and help with vital tasks, but they are not vessels of honor.

Typically, vessels of dishonor do end up being destroyed (which is not necessarily hell!), but this is not because the potter made them for such a purpose, but because unclean vessels, when they have served their purpose, are usually not useful for anything else.

And what makes one vessel clean or unclean? As H. H. Rowley pointed out above, God allows humans to determine what kind of vessel they will be, and then He uses those who have made themselves vessels of dishonor.

And what makes one vessel clean or unclean? As H. H. Rowley pointed out above, God allows humans to determine what kind of vessel they will be, and then He uses those who have made themselves vessels of dishonor.

A careful reading of Romans 9:22 reveals this very point. W. E. Vine, in his Expository Dictionary of New Testament Words, says that the word “destruction” is used “metaphorically of men persistent in evil (Rom 9:22), where ‘fitted’ is in the middle voice, indicating that the vessels of wrath fitted themselves for destruction” (Vine’s Expository Dictionary, 2:165)

None of this Relates to Person’s Eternal Destiny

Again, none of this has anything to do with whether or not a person goes to heaven or hell after death. The way a vessel is used refers primarily to how God uses individuals, kings, and nations in this life. Marston and Forster add this:

The basic lump that forms a nation will either be built up or broken down by the Lord, depending on their own moral response. If a nation does repent and God builds them up, then it is for him alone to decide how the finished vessel will fit into his plan … God alone determines the special features / privileges / responsibilities of a particular nation (Forster & Marston, God’s Strategy, 74).

To read more on Romans 9, get my book The Re-Justification of God.

If you want to read more about Calvinism, check out other posts in this blog series: Words of Calvinism and the Word of God.

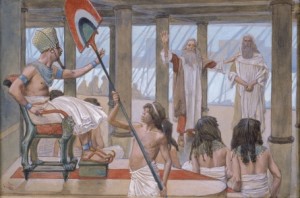

In Romans 9, Paul writes about the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart for the purposes of making God’s glory known. This seems rather harsh to some.

In Romans 9, Paul writes about the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart for the purposes of making God’s glory known. This seems rather harsh to some. But in response to this, Calvinists argue back that although the text says that Pharaoh hardened his own heart before God hardened it, before Moses even went to speak to Pharaoh, God told Him that He planned to harden Pharaoh’s heart (Exod 4:21; 7:3).

But in response to this, Calvinists argue back that although the text says that Pharaoh hardened his own heart before God hardened it, before Moses even went to speak to Pharaoh, God told Him that He planned to harden Pharaoh’s heart (Exod 4:21; 7:3). The issue is not about who hardened Pharaoh’s heart first—though that is where most of the ink has been spilled—but rather about what it means for Pharaoh’s heart to be hardened.

The issue is not about who hardened Pharaoh’s heart first—though that is where most of the ink has been spilled—but rather about what it means for Pharaoh’s heart to be hardened. Pharaoh’s eternal destiny is not under discussion in Exodus or in Romans, and so Pharaoh’s heart can be hardened so that God’s purposes are achieved, while still leaving plenty of room for Pharaoh to believe in God’s promises and become one of God’s people.

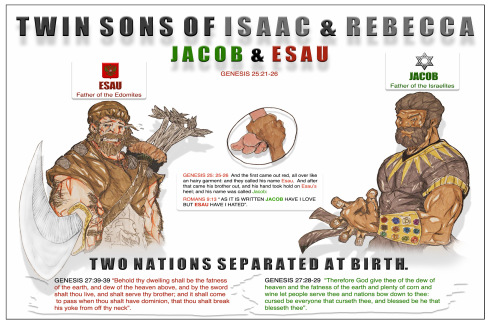

Pharaoh’s eternal destiny is not under discussion in Exodus or in Romans, and so Pharaoh’s heart can be hardened so that God’s purposes are achieved, while still leaving plenty of room for Pharaoh to believe in God’s promises and become one of God’s people. Paul writes a difficult statement in Romans 9:13:

Paul writes a difficult statement in Romans 9:13:

How can we choose between the two views above? Does God hate Esau and Edom, or does He simply love Edom less than He loves Israel?

How can we choose between the two views above? Does God hate Esau and Edom, or does He simply love Edom less than He loves Israel?

The GPS said it would take about 3 hours to arrive.

The GPS said it would take about 3 hours to arrive. Yet when we arrived, I was absolutely shocked to discover that there were dozens of cars and campers already there. And most of the cars were the little two-door and four-door sedans you see driving around a major city; none of them could have traversed the road we had just traveled.

Yet when we arrived, I was absolutely shocked to discover that there were dozens of cars and campers already there. And most of the cars were the little two-door and four-door sedans you see driving around a major city; none of them could have traversed the road we had just traveled. Yes, I am talking about the Bible.

Yes, I am talking about the Bible.