There is a fourteenth-century poem by Guillaume de Machaut that tells about how the Black Death ravaged a northern French city (I could not find an English translation of this poem online, but I read about the poem in an excellent book I’m reading, Saved from Sacrifice by Mark Heim.)

Curiously, the poem seems to blame the Jews in the city for the Black Death. It condemns Jews in the city for killing large numbers of its citizens by poisoning the rivers, and it also enumerates various grotesque practices by the Jews.

But then the poem goes on to state about how the citizens of the city rose up and carried out a massacre of the Jews, and how this massacre was clearly God’s will because it was accompanied by heavenly signs. Furthermore, after the massacre concluded, the plague left the city, which was seen as proof to the citizens that the Jews were the ones guilty for bringing the plague upon them in the first place.

It’s a tragic poem, but I hope you can read between the lines and see that the events it describes are not historically accurate.

We all understand what really happened.

Reading Between the Lines

Most likely, the Black Plague really did ravage the town, much as it ravaged many towns at that time. But as usually happens in such situations, people started looking for someone to blame, and in this town, because the Jewish people were seen as “outsiders under the curse of God,” they became the scapegoats.

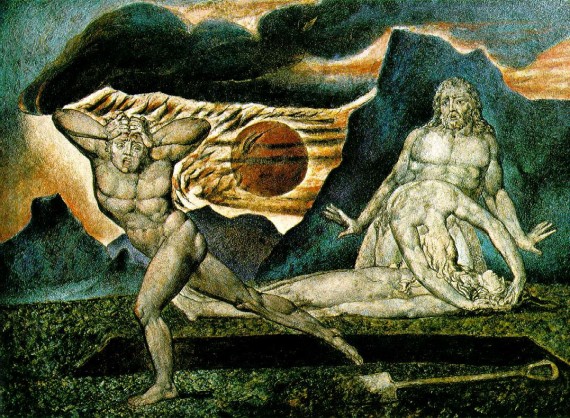

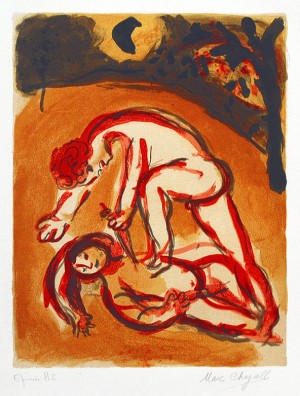

But they could not just be killed. They first had to be demonized.

So the villagers came up with stories about how the Jews poisoned the river and engaged in various grotesque and illicit practices.

Once the Jews were properly demonized, they could be “righteously” killed.

After the Jews were killed, any sort of natural occurrence was viewed as a sign from heaven that God approved of the massacre. Maybe the day of the massacre began with dark clouds and fog, but as the massacre commenced, the sun shone through the clouds. Maybe that night a star fell from the sky. Maybe an eagle landed on the house of the town mayor. But whatever the events were, they were interpreted as heavenly signs.

Later, of course, the plague went away, and this also was interpreted as a sign that the Jews were to blame. We, of course, look back and recognize that the Black Plague had simply ran its course, as it did everywhere else.

I am not sure of the exact historical events, but it doesn’t really matter. We are able to read the poem by Guillaume de Machaut and see through the events to what actually occurred: “Frightened citizens persecuted a religious minority, projecting blame for the plague on them and seeking by violence to stop the dissolution of their community” (Heim, Saved from Sacrifice, 55).

You do not need to have been there to have this historical insight into the true story behind this tragic poem.

Stereotypes of Scapegoating

In his book, Saved from Sacrifice, Heim explains our “insight” into what “really happened” this way:

We don’t take this story at face value. We see through it precisely when it takes up certain anti-Semitic themes. The moment the Jews are mentioned in connection with the plague, the moment they are accused of poisoning the water supply, of bearing physical deformities, of practicing sexual perversions, bells go off.

These are stereotypes, trotted out again and again as preludes to pogroms.

They are characteristic “marks of the victim” brought forward as justification for the violence. We do not credit them as reports of fact. We have learned to read such a text quite against the grain of the writer who composed it, for whom these matters were as real as the death of the neighbors on the one hand and celestial omens on the other. We practice a hermeneutic of suspicion against persecution (Heim, Saved from Sacrifice, 55).

Yes, that is true. We do. When it comes to these sorts of texts in history and literature, we are fairly adept at “seeing through” the account to what fears and scapegoating mechanisms lie behind the text.

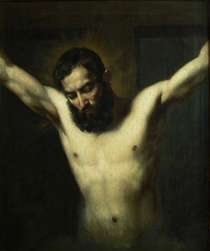

And it is right that we should do so, because this is what Jesus revealed through His death on the cross. The death of Jesus on the cross “rescues us from sin” in that it reveals to us the scapegoating, blame-game mechanism behind most of our sin and violence. We saw it happen to Jesus, and so we are able to see it happen to other people.

We recognize this scapegoating mechanism at work when we read about a town in the middle ages killing Jews because they are accused of causing the black plague. We recognize this scapegoat mechanism when we read about the Nazis in Germany blaming the Jews for the financial problems and cultural upheaval in that country. We recognize the scapegoating mechanism when people burn women for being “witches.” We recognize the scapegoat mechanism when we read about governments justifying genocide against the native people living in the land.

In all these cases, we practice this “hermeneutic of suspicion against persecution” that Heim talks about in his book. And because of the revelation of Jesus Christ on the cross, we have become quite good at recognizing this scapegoat mechanism when we read about it in historical documents.

… Except in one place.

Reading the Bible with Scapegoating in Mind

Have you ever noticed that ALL of the characteristic “marks of the victim” are brought forward over and over again in the Old Testament as justification for the violence carried out against the enemies of Israel?

The stereotypes are trotted out as preludes to pogroms, but rather than “see through the text” at what is really going on, we nod our head in astonishing agreement with the text.

Like a pre-programmed robot, we say, “Yes … the Canaanites were very evil. Yes, they practiced horrible things. Grotesque things. They worshipped demons and were demonic themselves. Yes, they needed to die to cleanse the land and protect the people of Israel. Yes, God wanted them all to die. Yes, God even sent signs and miracles to Israel when they slaughtered the Canaanites showing that such actions were righteous and divinely ordained.”

Why can we see “through” the blatant lies and false accusations and scapegoating violence when we read such historical accounts, but not when we read the Bible?

Has it ever occurred to you that we read the Bible with blinders on?

It has recently occurred to me, and now, when I read the Bible, especially the violent portions in the Old Testament, my eyes tear up. It’s like reading an account of Nazi Germany … from the viewpoint of the Nazis.

Yet we Christians whitewash the entire thing and say that all the killing, and genocide, and slaughter was “justified.” That it was righteous. That God wanted it. Commanded it. Demanded it.

“And look!” we say. “There’s proof! The waters parted! The walls fell down! The sun stood still! There was peace in the land afterward!”

Yes, which is exactly what every group always says whenever they carry out scapegoating genocide. Those who carry out genocidal violence “believe they are (a) revenging an appalling offense against their entire community [and God as well], (b) expelling the contaminating evil from their midst, and (c) obeying a divine mandate” (Heim, Saved from Sacrifice, 51-52).

Note that this is also what happened when Jesus was killed. His accusers raised a large number of baseless and patently false accusations against Him, then felt that it was necessary to expel His evil from their midst, and they did all this in obedience to the command of God (so they claimed).

Jesus was the ultimate scapegoat … to reveal that we all scapegoat!

When we read the account of the crucifixion of Jesus, we see right through the murderous, scapegoating violence. We see that Jesus was not guilty for that which He was condemned and killed.

I See Dead People

And now we are back to my question: Why can we see “through” the blatant lies and false accusations and scapegoating violence when we read the account of the crucifixion, but not when we read the rest of the Bible?

Again, I think we are reading the Bible with blinders on.

We read and preach and teach these horrible texts without a bat of an eye or a sign of a tear. We talk about what these texts “mean” and “how to apply them to our lives” and what they “reveal about God.”

But we don’t think about what they are really, truly saying.

We don’t see what they really, truly reveal. The victims disappear, and we become guilty of the same crime as those who crucified Jesus. We say they had it coming. We say it was necessary to cleanse the land. We say that God decreed it. We say that God blessed it.

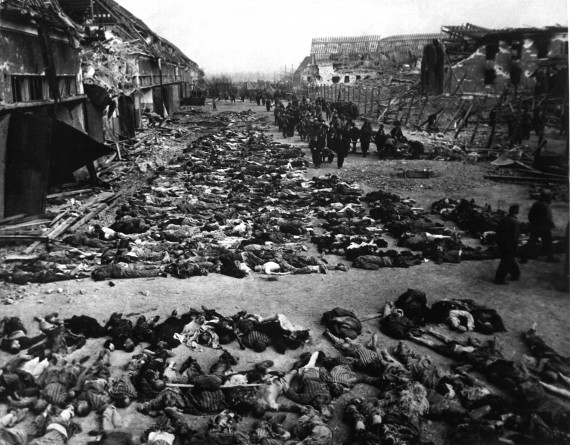

And we ignore the piles of bloody bodies rotting in the hot desert sun.

I am convinced that we will never, ever see the Bible for what it really is until we are able to read it and say, “I see dead people.”

The Bible was not written primarily to reveal God to us, but was written to reveal the same thing that Jesus revealed on the cross, which is that we scapegoat people in the name of God. And until we see this, we will never read the Old Testament correctly, nor will we ever understand God properly.

You will never understand the Old Testament until you see the victims.

The piles of bloody victims.

The masses of people unjustly murdered.

You will never understand the Old Testament until you see the genocide.

And don’t try to sidetrack this with discussions about inerrancy or inspiration or any of the other fancy theological words we use to divert our attention away from the bodies of bloody men, women, and children strewn all over the pages of our Holy Bible.

This is not about the sanctity of God’s Word, but about the sanctity of God’s people … namely, ALL people.

This is not about the sanctity of God’s Word, but about the sanctity of God’s people … namely, ALL people.

Once you are able to see this about the Bible, there will be no going back. Not just with how you read the Bible, but also with how you view life.

Once you begin to see dead people in the Bible, your eyes are opened and you begin to see dead people today. You will begin to see that the people we blame for the ills of society and the problems of culture and the war “over there” and the problems in our town, might not be the ones at fault after all…

Maybe, just maybe, those people over there are not to blame. Replace “those people over there” with whatever group you want … the communists, the Muslims, the liberals, the Tea partiers, the gays, the illegal immigrants.

Maybe the fault is not with them … but with us.

This is the perspective that comes from holding the mirror of Scripture before our face and taking a good, long look at how the Israelites scapegoated the Canaanites and how both the Jews and the Romans scapegoated Jesus, and how we ourselves scapegoat other people today.

Thankfully, there are countless Christians around the world who are starting to take the blinders off. They are reading the Bible with renewed eyes and are seeing that the violence of the Old Testament text is actually this genocidal, murderous, scapegoating violence.

And look … I firmly believe in inspiration and inerrancy. I truly do. I just think that the divinely inspired text inerrantly reveals something that few Christians want to see. The Bible reveals the dead people. It is a revelation of death and violence, and where death and violence come from.

The answer? They come from us. Not from God. From us.

But we don’t want to see this. We don’t want to admit it. So we put our blinders on and go back to nodding our heads along with texts that talk about the divinely-sanctioned slaughter of thousands of victims. We participate in the scapegoating, and we put to death the Son of Man all over again.

Until you see dead people, you are no better than those who cried out at the trial of Jesus, “Crucify Him! Crucify Him! Crucify Him!”

Until you see dead people, you will be the one who puts people to death.

For all the mentions of human violence, references to divine violence appear almost twice as often.

For all the mentions of human violence, references to divine violence appear almost twice as often. Though innocent of any wrongdoing, God, in Jesus, let us blame Him for every wrongdoing.

Though innocent of any wrongdoing, God, in Jesus, let us blame Him for every wrongdoing.

We Christians owe the world an apology.

We Christians owe the world an apology.

One of the key sections of A More Christlike God is where Brad Jersak discusses the all-important issue of “the wrath of God.” This idea is found in numerous places in the Bible, and is one of the key issues in this debate about what God is like. Many people assume that the phrase “the wrath of God” indicates that God is angry at us. Jersak presents a compelling case for why this is not a proper understanding of that term. He rightly critiques the idea that “the wrath of God” is God withdrawing His mercy. God never withdraws His mercy. God’s mercy is unfailing and everlasting. His mercy endures forever (Psalm 136).

One of the key sections of A More Christlike God is where Brad Jersak discusses the all-important issue of “the wrath of God.” This idea is found in numerous places in the Bible, and is one of the key issues in this debate about what God is like. Many people assume that the phrase “the wrath of God” indicates that God is angry at us. Jersak presents a compelling case for why this is not a proper understanding of that term. He rightly critiques the idea that “the wrath of God” is God withdrawing His mercy. God never withdraws His mercy. God’s mercy is unfailing and everlasting. His mercy endures forever (Psalm 136).