(#AmazonAdLink)  I am taking a short break from teaching through Ephesians to record an audiobook for my book (#AmazonAdLink) The Atonement of God. A reader has generously offered to sponsor the recording of this audiobook. This podcast episode provides a preview of the audiobook by giving you Chapter 5: What a Non-Violent View of the Atonement Reveals about Scripture.

I am taking a short break from teaching through Ephesians to record an audiobook for my book (#AmazonAdLink) The Atonement of God. A reader has generously offered to sponsor the recording of this audiobook. This podcast episode provides a preview of the audiobook by giving you Chapter 5: What a Non-Violent View of the Atonement Reveals about Scripture.

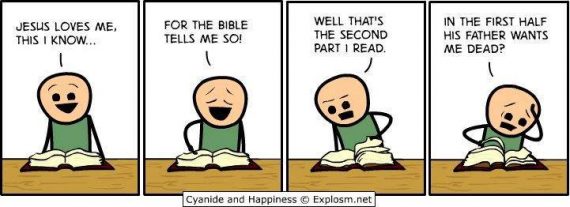

In this podcast episode, you will learn how to read and understand the violent portions of Scripture in light of Jesus Christ and Him crucified.

On this cross, Jesus shows us how to properly read the Bible. If you struggle with the violent portions of Scripture, it helps to read them through the lens of Jesus Christ on the cross.

If you want to sponsor a reading of one of my books into audiobook format, please reach out to me through the contact form.

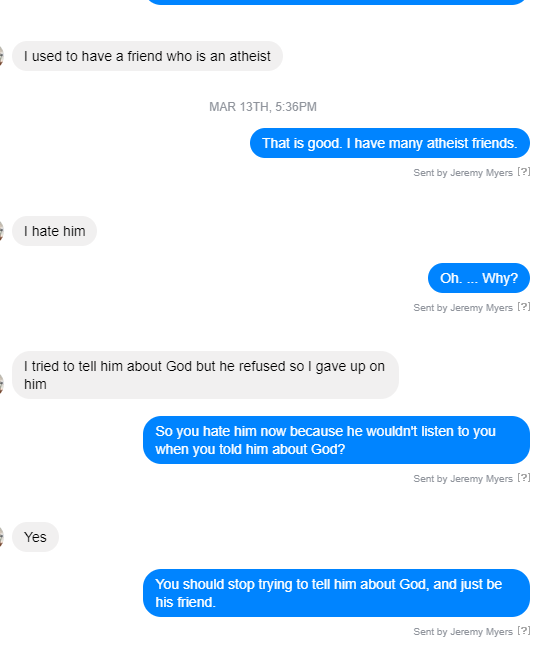

(Note: I include Greg Boyd’s “Divine Withdrawal” view in this category. He argues that God finally got fed up with the evil of mankind, and so He withdrew His divine hand of protection that was holding back the destructive floodwaters, thereby allowing them to destroy humanity. In this view, God didn’t do the destroying Himself; He simply stepped back to let the destroyer have its way with humanity. In a personal conversation with Greg Boyd, I related to him the following video clip, and he agreed that for the most part, it represents his position.)

(Note: I include Greg Boyd’s “Divine Withdrawal” view in this category. He argues that God finally got fed up with the evil of mankind, and so He withdrew His divine hand of protection that was holding back the destructive floodwaters, thereby allowing them to destroy humanity. In this view, God didn’t do the destroying Himself; He simply stepped back to let the destroyer have its way with humanity. In a personal conversation with Greg Boyd, I related to him the following video clip, and he agreed that for the most part, it represents his position.) Is this just a divine example of the bad parenting advice “Do as I say; not as I do?”

Is this just a divine example of the bad parenting advice “Do as I say; not as I do?” And when we look to Jesus, and specifically the most violent aspect of the life of Jesus, His crucifixion, and we carefully see what is being done to Jesus on the cross, we discover something surprising.

And when we look to Jesus, and specifically the most violent aspect of the life of Jesus, His crucifixion, and we carefully see what is being done to Jesus on the cross, we discover something surprising.

Looking at our face in the mirror of Genesis 6–8, we must ward ourselves against the common human practice of condemning others when bad things happen to them. We must stop saying, “Well, he lost his job and got cancer, so God must be punishing him for some secret sin.” (Remember Job?) Instead, when bad things happen to people, we must, like Jesus, enter into their hellish pain and sorrow, and help them or love them in in any way we can.

Looking at our face in the mirror of Genesis 6–8, we must ward ourselves against the common human practice of condemning others when bad things happen to them. We must stop saying, “Well, he lost his job and got cancer, so God must be punishing him for some secret sin.” (Remember Job?) Instead, when bad things happen to people, we must, like Jesus, enter into their hellish pain and sorrow, and help them or love them in in any way we can.

But then many Christians turn right around and say, “But in the future, Jesus is going to return to this earth, and slaughter millions of people. There will be the greatest, bloodiest war the world has ever seen. When Jesus returns at the battle of Armageddon, the Valley will be filled with blood up to the horse’s bridle.”

But then many Christians turn right around and say, “But in the future, Jesus is going to return to this earth, and slaughter millions of people. There will be the greatest, bloodiest war the world has ever seen. When Jesus returns at the battle of Armageddon, the Valley will be filled with blood up to the horse’s bridle.”

In this text, Jesus provides a summary of how He reads and understands the Old Testament. This is “The Old Testament according to Jesus.” And according to Jesus, the Bible is filled with violent bloodshed.

In this text, Jesus provides a summary of how He reads and understands the Old Testament. This is “The Old Testament according to Jesus.” And according to Jesus, the Bible is filled with violent bloodshed.