What a blog post title! Epistolary Diatribe … what???

What a blog post title! Epistolary Diatribe … what???

But have no fear … it’s not as scary as it sounds. This article will really help you understand the letters of Paul. I promise.

Let me begin by asking you a question … If you had no quote marks, how would you indicate in a book or letter that you were quoting someone? Well, you would probably just state the quote anyway, and then use words like “said” to tell you reader you are quoting something.

Here’s an example:

Gary said I love elephants.

But notice that without quote marks, the sentence loses clarity.

It could be understood this way:

Gary said, “I love elephants.”

Or this way:

Gary said [that] I [Jeremy] love elephants.

Do you see? Without quote marks, one sentence can have at least two different meanings.

But it gets trickier than that. What if I am writing a dialogue between two or more people, and I now have to record what each person says … still without quote marks.

Here is an example:

Gary said I love elephants.

Tom said I love them too.

But I said both of them are wrong.

So you see? What EXACTLY was said is a little vague, but the context gives you some idea of what Gary, Tom, and I were talking about.

Ah, but now watch this …. if I quote someone without any quote marks, and if I don’t use the word “said” or even tell you who said it, I can almost guarantee you will know who said it and what they said:

That’s one small step for a man; one giant leap for mankind.

Do you know who said that and the context in which it was said? Of course you do (I hope). I didn’t have to use quote marks, and I didn’t have to use the word “said.” You automatically knew. (And yes, I quoted it correctly … according to the man who said it.)

Now, take the little bit you’ve learned here about quote marks and easily-recognized quotations and think back to the days of the early church when Paul was writing letters to the various churches he had planted. Many times, Paul wrote these letters to correct and refute some of the false ideas and teachings that were being taught within the various churches.

But guess what? There were no quote marks in Koine Greek (the language Paul used to write his letters).

So what did he do?

Well, he used a style of writing which was quite common for other letter writers in his day, which modern scholars have labeled “Epistolary Diatribe.” This is a fancy way of saying “A letter written to correct the wrong ideas of someone else.” And since this method of writing letters to refute others was quite common, people quickly and easily recognized it when it was happening in a letter.

This is especially true when we recognize that trained “readers” often “performed” the dialogue portions of the letters to a listening audience … many of whom could not read.

This is especially true when we recognize that trained “readers” often “performed” the dialogue portions of the letters to a listening audience … many of whom could not read.

Some of the distinguishing marks of Epistolary Diatribe are as follows:

- Famous quotes from the letters, writings, teachings of the person being refuted

- The word “say” or “said” might be used (e.g., “You have heard it said,” Or “But someone will say.”)

- A refutation begun with an adversative conjunction (e.g., “But” or “Of course not!”)

- A gentle mocking, or name-calling, or the person being refuted (e.g., “Who are you, Oh man?” or “Oh foolish man!”)

These four clear signs are not always present, and so it is sometimes difficult to know whether a certain verse is Paul’s idea or a quote from someone Paul is refuting, but there are several very clear examples of this sort of “Epistolary Diatribe” going on in the New Testament.

Below are three clear examples (and yes, I know the last one is not from Paul, but it still gives a good example):

Clear Examples of Epistolary Diatribe

Romans 9:19-20

In this passage, Paul introduces the person who is objecting to Paul’s words by saying “You will say to me then.”

After this, Paul quotes what this objector is saying: “Why does He still find fault? For who has resisted His will?”

Paul begins his response in the typical way, by using an adversative conjunction followed by a gentle name-calling of the person. Paul says, “But indeed, O man, who are you to reply against God?”

From this, we see that Paul thinks that God has set up the world in a way that God’s will can be resisted. The objector disagrees and says that nobody can resist God’s will. Paul responds with a bit of irony, telling the objector, “By saying nobody can resist God’s will when God has said that people can resist His will, you are resisting God’s will.” It’s a brilliant move by Paul. I write more about this in my book, The Re-Justification of God, which looks at Romans 9.

1 Corinthians 15:35-36

Paul’s letter to the Corinthians is full of Epistolary Diatribe, especially since he is responding to a letter they wrote to him. So he quotes some of their letter, or what he heard that some people were teaching in Corinth, and then he responds to it.

In Paul’s discussion about the resurrection, he introduces the quote from another teacher by writing, “But someone will say.”

Then Paul quotes what they are saying, “How are the dead raised up? And with what body do they come?” In other words, the objector says that the idea of a resurrection is foolish unless we understand how it works and what our new bodies will be like.

Paul then sets out to refute this objection with a little gentle name-calling. He introduces his refutation with the words “Foolish one” and then goes on to explain more about the resurrection.

Note that the adversative conjunction was missing, but it was still quite obvious that Paul was engaging in dialogue with this other teacher.

James 2:18-20

It is not just Paul that uses Epistolary Diatribe. As mentioned earlier, this form of writing was very common. James, the brother of Jesus, uses it as well in his letter.

A clear example is found in James 2:18-20. In fact, recognizing Epistolary Diatribe in James 2 helps clear up a lot of the confusion surrounding James 2 and the role of faith and works in the life of the believer.

James is writing about the relationship between faith and works, and he introduces the objection by someone else in the normal way. He writes, “But someone will say.” And then James goes on to quote this ideas of this person who is objecting.

The interesting thing about this is that few Bible translations understand where the quote from this imaginary objector ends. If you consult some of the various Bible translations, you will see that in English, the end quote is inserted at different places in different translations.

The NKJV puts the end quote half-way through verse 18. The NAS puts the end quote at the end of James 2:18. But when we understand the signs of Epistolary Diatribe, we recognize that the quote of the objector goes all the way through verses 18 and 19. How do we know this?

Because James 2:20 has the adversative conjunction and then the gentle, derogatory name-calling. James indicates that he is now refuting the objector when he writes, “But do you want to know, O foolish man, that faith without works is dead?”

When we realize that James 2:19 and what it says about the faith of demons is not the ideas of James, but the ideas of someone who disagrees with James, this helps our overall understanding of the passage. I wrote more about this in my article “Even the demons believe” and have also taught about it in my study on James 2:14-26.

So those are just three clear examples of Epistolary Diatribe in the New Testament. There are several other clear examples, but I just wanted to point these out.

Now, there are many, many other passages in the Bible that likely contain Epistolary Diatribe.

Other Possible Epistolary Diatribe Passages

The problem with several of these other possible passages that contain Epistolary Diatribe is that they don’t always contain all four of the markers that I mentioned above. They might only contain one or two. Or none.

But again, what we have to recognize is that while it might be difficult for us to discern when Epistolary Diatribe is taking place, it was not difficult for the original audience.

They likely would have had someone play-act the dialogue out for them, with the reader using different voices, or maybe different hand gestures to indicate when a different person was talking. Also, they would have quickly and easily recognized the ideas and quotes from the teacher that Paul was refuting in his letter.

What if I wrote a letter to you which said this:

Sometimes I look at everything going on in the world, and I am afraid for the future. We must remember, however, that we have nothing to fear, but fear itself. And besides, God loves us, and perfect love casts out fear, because fear has to do with punishment. Nevertheless, although I know this to be true, I am still afraid sometimes. So when I am afraid, I remind myself of two things. First, I say “No fear!” and then I also say “Fear not!”

There were four intentional quotes from other sources in that paragraph. The first was from Franklin D. Roosevelt, the second from 1 John 4:18, the second was the old marketing slogan from the 80’s and 90’s, and the final quote came from Isaiah 41:10.

It is possible you picked up on all of them, though maybe you only recognized one or two. Now, if I had changed my voice in all the quotes, you would have recognized that I was quoting someone else, even if you didn’t know the source of the quote.

This, I believe, is exactly what was happening in the early church as the letters of Paul circulated around and were read in the various churches.

So here are a few possibilities of where this is happening.

Romans 1:18-32

Paul’s letter to the Romans almost certainly includes numerous Epistolary Diatribes in which Paul quotes and then refutes a prominent teacher in Rome.

Romans 1:18-32 is sort of the introduction to what this other teacher was saying. Therefore, much of what we read in Romans 1:18-32 is not Paul’s ideas, but the ideas of someone that Paul wants to refute.

Romans 1:18-32 is sort of the introduction to what this other teacher was saying. Therefore, much of what we read in Romans 1:18-32 is not Paul’s ideas, but the ideas of someone that Paul wants to refute.

This is extremely significant, for it is only here in Romans that wrath is clearly attributed to God. Also, it is here that we read about God handing people over to their sin.

And all of these ideas do not come from Paul, but rather from a legalistic teacher whom Paul sets out to refute in his letter to the Romans.

And indeed, in Romans 2:1, we do have the clear sign that Paul picks back up with his own ideas to refute the ideas he just quoted. He does a little gentle name-calling and sets out to refute what he just quoted. “Therefore you are inexcusable, Oh man, whoever you are who judge…”

To read more on this, here are two articles which lay this out more:

Do you read Romans like an Arian?

A Rending of Romans 1:1-4:3 in Dialogue Form

This way of reading really helps bring clarity to Paul’s argument in Romans and his theology as a whole.

Romans 3:1-9, 27-31

Another sign that Paul is using Epistolary Diatribe in Romans in found in Romans 3:1-9, and 27-31. There is a back-and-forth dialogue that seems quite obvious and natural in the letter.

When we rightly discern which ideas are Paul’s and which ideas belong to the legalistic religious teacher Paul is refuting, the entire text makes much more sense.

Read the two articles linked to above for more help on this.

1 Corinthians 6:12-14

As with Romans, the book of 1 Corinthians is full of Epistolary Diatribe. With almost every new topic Paul addresses, he first quotes what was being taught in Corinth, or what they wrote to him in a letter, and then he sets out to answer their question or refute what they are doing and teaching.

Here is how to read 1 Corinthians 6:12-14 in light of this:

Corinth: All things are lawful for me.

Paul: But all things are not helpful.

Corinth: All things are lawful for me.

Paul: But I will not be brought under the power of any.

Corinth: Foods for the stomach and the stomach for foods.

Paul: But God will destroy both it and them.

Paul: (Extrapolating out to sexual immorality from this point about the stomach and food) Now the body is not for sexual immorality but for the Lord, and the Lord for the body. And God both raised up the Lord and will also raise us up by His power.

1 Corinthians 7:1-2

We can do something exactly similar in 1 Corinthians 7:1-2.

Paul: Now concerning the things of which you wrote to me [and I quote]:

Corinthian Letter: “It is good for a man not to touch a woman.”

Paul cautions against this: Nevertheless, because of sexual immorality, let each man have his own wife, and let each woman have her own husband.

Do you see? In this way, it is not Paul who is saying that it is good for a man to not touch a woman. It is the Corinthians who were saying this, and Paul is cautioning them against such practices. He goes on to explain why in the following verses.

I could go on and on. There are numerous other examples of Epistolary Diatribe in Scripture. For an exhaustive (it’s also an exhausting read … and a workout to even lift) explanation of this technique in Paul’s letters, get The Deliverance of God by Douglas Campbell. It’s an expensive book, and I don’t recommend that everyone read it, because of how technical it is, but he does provide a very good explanation and defense of Epistolary Diatribe.

Why am I bringing this up?

I had an on-stage 5-minute discussion with Greg Boyd at his ReKnew conference last September, and in my closing comment, I hinted at my belief that something else is going on in Romans 1 than what Greg Boyd thinks is going on. My discussion with Greg Boyd begins at about the 20:00 mark.

Romans 1:24 says that God gave people up, or handed them over, to their vile passions and depraved hearts. Greg Boyd thinks that this is Paul’s own idea. I think that since this idea does not at all reflect what we see in Jesus, or even what we see elsewhere in the writings of Paul, that we must conclude that something else is going on in the text.

And what is that something else? It is Epistolary Diatribe.

Romans 1:24 and the surrounding verses are not the ideas of Paul, but the ideas of a legalistic law-based religious teacher in Rome, whom Paul is quotes so that he can then refute him.

There are extensive clues all over in Romans 1-3 that this is happening, and I think that this approach helps make sense of these opening chapters of Romans in light of everything else in this letter.

So I have mentioned it to Greg, and I have mentioned it to you, but let me say it again: I do not believe that God hands us over to sin and Satan. He does not deliver us up to the destroyer. He does not withdraw His protective hand. He does not “Release the Kraken!” to have its way with us.

As we see in Jesus Christ from first to last … God always forgives, only loves, and will never, ever, ever leave us or forsake us, but will be with us, even unto the end of the age.

In one of his recent email newsletters (

In one of his recent email newsletters (

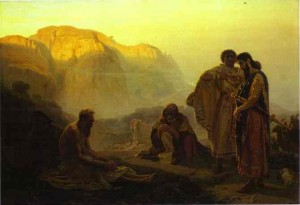

“But” (as my wife pointed out to me once), “What about God’s deal with the devil at the beginning of the book? Didn’t God allow Satan to do all these bad things to Job? How is this not divine violence?” Excellent point, Wendy! My answer is that this proves that the book of Job is actually about the satanic activity of accusing and blaming others in the name of God. Satan is there in the beginning as the accuser, and the satanic presence is seen throughout the book as everyone is accusing Job, and Job is accusing God.

“But” (as my wife pointed out to me once), “What about God’s deal with the devil at the beginning of the book? Didn’t God allow Satan to do all these bad things to Job? How is this not divine violence?” Excellent point, Wendy! My answer is that this proves that the book of Job is actually about the satanic activity of accusing and blaming others in the name of God. Satan is there in the beginning as the accuser, and the satanic presence is seen throughout the book as everyone is accusing Job, and Job is accusing God. I had a very similar conversation with Greg at the ReKnew conference, in which he stated that he also leaves natural disasters completely unexplained. He says, and I agree, that there are too many variables to determine the cause of any natural disaster. The only exception, Greg says, are the natural disasters found in the Bible. The Bible claims that these (in some way) came from God, and so therefore, they did. Call it Satan, the destroyer, or God withdrawing, these, and only these, natural disasters have some sort of divine origin. For many reasons, I find this explanation highly troubling, and extremely unhelpful. After all, if the CWG thesis helps us understand the Bible but not life, then it is not helpful and cannot be accepted.

I had a very similar conversation with Greg at the ReKnew conference, in which he stated that he also leaves natural disasters completely unexplained. He says, and I agree, that there are too many variables to determine the cause of any natural disaster. The only exception, Greg says, are the natural disasters found in the Bible. The Bible claims that these (in some way) came from God, and so therefore, they did. Call it Satan, the destroyer, or God withdrawing, these, and only these, natural disasters have some sort of divine origin. For many reasons, I find this explanation highly troubling, and extremely unhelpful. After all, if the CWG thesis helps us understand the Bible but not life, then it is not helpful and cannot be accepted. Frankly, most people, myself included, would rather have the pain and punishment come directly from God. If God is going to let satan kill people, God should have the respect for humanity to just do it Himself. If Greg’s view of God is correct, then I say this to God, “Hey God, man up. Don’t send a hit man to do your dirty work.”

Frankly, most people, myself included, would rather have the pain and punishment come directly from God. If God is going to let satan kill people, God should have the respect for humanity to just do it Himself. If Greg’s view of God is correct, then I say this to God, “Hey God, man up. Don’t send a hit man to do your dirty work.”  Anyway, the death of Jesus is the center of Scripture and theology, and I base everything I think and teach on what Jesus accomplished on the cross. Or at least, I try to. I believe every word of Scripture; I just believe some of these words differently than Greg does. This doesn’t mean I’m wrong, or that he is. It just means there is room for further discussion and humble learning. If Greg decides to continue this conversation, I promise not to mention Girard.

Anyway, the death of Jesus is the center of Scripture and theology, and I base everything I think and teach on what Jesus accomplished on the cross. Or at least, I try to. I believe every word of Scripture; I just believe some of these words differently than Greg does. This doesn’t mean I’m wrong, or that he is. It just means there is room for further discussion and humble learning. If Greg decides to continue this conversation, I promise not to mention Girard.