One of the members of my online discipleship group recently asked me about 1 John 1:7-10 and how the blood of Jesus cleanses us from sin. Here is what he wrote:

I really appreciate your ministry and have been blessed by your books. I have a question for you regarding 1 John 1:7, where it says the blood of Jesus cleanses us from sin. I just listened to your podcast about the two different words for forgiveness, but I’m wondering how this verse plays into it all, since it uses the word “cleanses” – what do I need to know to understand this well? -Eli

Thanks for the question, Eli!

1 John 1:7-10 does get discussed in various ways through my online course “The Gospel Dictionary,” but let me try to summarize here some of what I teach in that course. For a fuller understanding, you would need to take the lessons on Blood, Confess, Fellowship, Forgiveness, and Sin. Of course, not all of those lessons are available yet, but they will be soon… But while you wait, you can also read about forgiveness and sin in my book, (#AmazonAdLink) Nothing but the Blood of Jesus, which discusses these terms.

1 John 1:7-10 does get discussed in various ways through my online course “The Gospel Dictionary,” but let me try to summarize here some of what I teach in that course. For a fuller understanding, you would need to take the lessons on Blood, Confess, Fellowship, Forgiveness, and Sin. Of course, not all of those lessons are available yet, but they will be soon… But while you wait, you can also read about forgiveness and sin in my book, (#AmazonAdLink) Nothing but the Blood of Jesus, which discusses these terms.

So here is my basic answer for how to understand 1 John 1:7-10.

Cleansing from Sin (1 John 1:7, 9)

Let us begin by quoting the pertinent verses:

But if we walk in the light as He is in the light, we have fellowship with one another, and the blood of Jesus Christ His Son cleanses us from all sin. … If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness (1 John 1:7, 9).

There are five key terms which help us understand 1 John 1:7-10. We must understand what is meant by the words “sin, blood of Jesus, confess, forgive, and cleanse.” Let us briefly consider all five.

Sin in 1 John 1:7-10

The term “sin” in 1 John does not simply refer to breaking God’s law or doing bad things. Most Christians understand the word “sin” this way, but this is not primarily the way the Bible defines sin.

In Scripture, as in 1 John, sin is primarily the activity and actions that lead to and involve accusing and scapegoating other people. Yes, John says that “sin is lawlessness” (1 John 3:4) but the laws were only given to keep us from accusing, condemning, scapegoating, and killing others in God’s name.

So lying and stealing are sinful, but only because they are part of the actions and behaviors that lead us to accuse, condemn, and scapegoat others. One premier place we see this in 1 John is when John gives the example of Cain murdering his brother Abel (Gen 4). This murder is the first sin in the Bible, and sets the stage for all sinful behavior that follows. (For a longer explanation, listen to my podcast episodes on Genesis 4.)

So sin is the ancient and universal human practice of wrongly accusing, condemning, scapegoating, and killing others in God’s name. This helps us understand what is meant by the term “the blood of Jesus.”

Blood of Jesus in 1 John 1:7-10

Few people actually believe that they engage in the practice of wrongly accusing, condemning, or scapegoating others. We believe that our judgments of others are righteous, valid, and correct. We believe that the people we accuse and condemn truly are guilty of the things we accuse them of.

And while it is true that they might be guilty of some of the things we accuse them of, the human tendency is to amplify the sinful behavior of others so that we can turn them into monsters, and dehumanize them, so that we can condemn them, or send them into exile, or even kill them in the name of God.

And while it is true that they might be guilty of some of the things we accuse them of, the human tendency is to amplify the sinful behavior of others so that we can turn them into monsters, and dehumanize them, so that we can condemn them, or send them into exile, or even kill them in the name of God.

But few humans recognize that we do such a thing. We don’t admit that our judgments are unjust. We think we rightly accuse and condemn others.

So Jesus came along to reveal the truth to us. And though He was innocent of all wrongdoing, we accused, condemned, and killed Him … and we did this all the name of God. But since He was completely innocent, His unjust crucifixion revealed that we humans have a problem with unjustly accusing and condemning people.

The blood of Jesus reveals this truth to us. And nothing but the blood of Jesus could reveal this truth to us. Only someone who was completely innocent could show us that we humans have a problem with unjustly condemning and accusing other people.

But the sad reality is that even though Jesus revealed this truth to us, few of us recognize our involvement in such behaviors. But we must recognize it, and we must agree that we are indeed guilty of these sorts of accusatory, condemning, scapegoating practices.

Confession in 1 John 1:7-10

The word “confess” means to agree. When Jesus revealed the truth to us by His blood, we are faced with a choice.

We can either agree with what Jesus has revealed, or we can disagree. We can either confess or we can deny that we do indeed engage in falsely accusing and condemning others.

Of course, if we deny that we are involved in such practices, then we’re simply deceiving ourselves and have not yet recognized the truth.

Forgiveness in 1 John 1:7-10

But if we do agree and confess that we have been involved in falsely condemning, accusing, and scapegoating other people, it is then and only then that we can begin to break free from such practices and start loving other people as God wants and desires.

There are two words for forgiveness in the Bible. One is freely extended by God to all people throughout time for all their sins, past, present, and future. The second is only experienced when we humans take certain actions to change our thought patterns or behavior.

There are two words for forgiveness in the Bible. One is freely extended by God to all people throughout time for all their sins, past, present, and future. The second is only experienced when we humans take certain actions to change our thought patterns or behavior.

It is this second type of forgiveness that is mentioned in 1 John 1:9. So while God has always and freely forgiven us for all our sins, we will not experience this forgiveness in our own lives unless we take some actions to see the truth about ourselves, and take steps to change our behavior.

But this change begins with agreeing or confessing that we practice sin.

Cleansing in 1 John 1:7-10

Only when we agree and confess that we do indeed engage in falsely accusing, condemning, and scapegoating other people will we begin to be cleansed from our practice of this sin in our lives.

The cleansing of our sin is not a spiritual cleansing, but is a cleansing and changing of our actual behaviors going forward. As we are cleansed in this way, we will grow in fellowship with God and with one another.

An Amplified Summary of 1 John 1:7-10

With these five terms in mind, we can now easily understand what John is saying in 1 John 1:7-10. Here is an amplified paraphrase:

1 John 1:7. God walks in the light and we can walk in the light with Him if we agree with the light of truth He has revealed. When we live in light of this, we will live in peace with God and with each other and will no longer engage in the sinful practices of accusing, condemning, scapegoating others, which was revealed to us through the blood of Jesus. When we turn from such practices, we will be cleansed from living in such violent ways.

1 John 1:8. Of course, not everybody wants to admit that they engage in such practices. We humans tend to think that our judgments of others are just, and that our accusations of them have the backing and support of God. But if we believe this way, then we are simply deceiving ourselves, and we have not yet understood the truth.

1 John 1:9. However, if we agree that we do indeed engage in the sinful practices revealed through the bloody death of Jesus on the cross, then God is faithful and just and will help us gain deliverance and freedom from our bondage and enslavement to these practices, and He will help us stop engaging in them any longer. (God has freely forgiven us of all these sins, but if we want to practically be cleansed from them, we need to admit that we engage in them, and then follow the example and teachings of Jesus in how to live with love and free forgiveness instead.)

1 John 1:10. So once again … if you deny that you engage in this basic human practice of accusing, condemning, and scapegoating others … if you think that the people you call “monsters” and “heretics” truly are guilty of everything you accuse them of … if you think that some people truly deserve to burn in hell for all eternity … if you think that war is righteous and good and we need to bomb some groups of evil people off the face of the planet … then you are calling God a liar, and you have not understood the first thing about God and what He taught through Jesus (cf. 1 John 4:7-11).

So what is John teaching in 1 John 1:7-10?

The blood of Jesus cleanses us from sin by exposing sin for what it is and then calling us to no longer live in the way of sacred violence. His blood cleanses us through calling us to practice non-violence.

The blood of Jesus is not a spiritual antidote to sin which somehow removes the polluting presence of sin from our lives.

The blood of Jesus is not a spiritual antidote to sin which somehow removes the polluting presence of sin from our lives.

No, the blood of Jesus exposes our sacred violence to us so that we can see in our own lives how we make scapegoat victims out of others, and then calls us to no longer live in this way. Instead, we are to walk in the light of Jesus and have fellowship with Him, with God, and with one another (1 John 1:3).

Of course, as John goes on to explain, if we deny what Jesus reveals to us through His blood, and say that we are not guilty of sacred violence toward others, then we simply have not yet seen the truth about the blood of Jesus and have not owned up to our own duplicity and participation in human scapegoating and violence.

Only once we admit it and own up to our role in making victims of others can we then be cleansed from it and work in fellowship with God and others (1 John 1:8-10).

But what about our PAST sins?

While this understanding helps cleanse our life from present and future sins, how does the blood of Jesus cleanse us from past sins?

In other words, while the understanding proposed here helps us turn from our violent, sinful ways in the future, what does 1 John 1:7-10 have to say about our past sins?

The answer is that the text doesn’t say anything about our past sins. It is only concerned with our present and future behavior.

John is primarily interested in make sure that his readers recognize how they have been involved in the violent, bloody, accusatory, scapegoating practices that run this world, and turn from such behaviors to walk in the light of God’s love.[1]

John is primarily interested in make sure that his readers recognize how they have been involved in the violent, bloody, accusatory, scapegoating practices that run this world, and turn from such behaviors to walk in the light of God’s love.[1]

Nevertheless, other passages in Scripture tell us how we are cleansed and forgiven by God from our past sins. Passages such as Romans 3:25-26, 2 Corinthians 5:19, and Colossians 2:13 reveal that God simply overlooks our sin, does not count our sin against us, and freely forgives all people of all their sin.

The instruction in 1 John 1:9 to confess our sins so that we might be forgiven is referring to a conditional type of forgiveness which is not the same thing as God’s free and unconditional forgiveness. Here in 1 John 1:7-10, the issue is not so much about being cleansed from our past sins, but about our present and future behavior as we seek to live in fellowship with God and one another.

So how are you going to live?

First of all, do you see what is revealed through the violent and bloody death of Jesus? Do you see how He revealed the truth that we humans accuse, condemn, scapegoat, and even kill other people in God’s name … but that none of this has anything to do with God, but is in fact the exact opposite of what God wants and desires?

Second, you you agree that you have engaged … and might still be engaging … in some of these practices today? Maybe you are engaging in this practice toward Muslims … or gays … or Democrats … or Republicans … or President Trump … or the Media … or your boss … or your neighbor … or … whomever.

Third, if you recognize you have engaged in some of these practices, then what are you to do about it? Well, that’s what the rest of 1 John is all about, which you can read on your own. But the bottom line is that you need to unconditionally love and freely forgive, just as God loves and forgives us.

But all of that will have to be saved for another study.

If you have questions or comments, leave them in the comment section below … and also, consider joining us in the online discipleship group where we regularly discuss these sorts of topics and passages. If you are already in the group, make sure you have signed up to take “The Gospel Dictionary” course, which is free for you to take inside the group.

Notes:

[1] The Greek word for “cleansing” in 1 John 1:7 is present indicative, and in 1 John 1:9 is aorist subjunctive. Though aorists can indicate past time, the subjunctive mood indicates probability or objective possibility. Therefore, due to the inherent contingency of the subjunctive mood, the implied timing is usually future, so that aorist subjunctive tends to have a future timing, and can even be used as a substitute with the future indicative. See https://www.ntgreek.org/learn_nt_greek/subj-detail-frame.htm

The basic message of Ephesians is that due to religion, humans have lived in rivalry and violence with each other since the foundation of the world, but now, in Jesus Christ, we have been shown a new way of living life so that all the hostilities can now cease.

The basic message of Ephesians is that due to religion, humans have lived in rivalry and violence with each other since the foundation of the world, but now, in Jesus Christ, we have been shown a new way of living life so that all the hostilities can now cease.

Paul’s point in these verses is that even though we humans accusation, blame, condemn and kill others in God’s name (Ephesians 2:1-3), God Himself does not behave that way toward us.

Paul’s point in these verses is that even though we humans accusation, blame, condemn and kill others in God’s name (Ephesians 2:1-3), God Himself does not behave that way toward us. By looking at Ephesians 1:7 and Ephesians 2:13, we now understand how the blood of Jesus redeems us.

By looking at Ephesians 1:7 and Ephesians 2:13, we now understand how the blood of Jesus redeems us.

But I bet you want a better explanation …

But I bet you want a better explanation … In reference the New Covenant, the blood of Jesus signaled that this New Covenant was now in effect. In essence, Jesus died to inaugurate or enact the New Covenant.

In reference the New Covenant, the blood of Jesus signaled that this New Covenant was now in effect. In essence, Jesus died to inaugurate or enact the New Covenant. There is charizomai forgiveness and aphēsis forgiveness. Charizomai forgiveness is based on the free grace (charis) of God and is freely extended to all people throughout all time for all sins, with no strings or conditions attached.

There is charizomai forgiveness and aphēsis forgiveness. Charizomai forgiveness is based on the free grace (charis) of God and is freely extended to all people throughout all time for all sins, with no strings or conditions attached.

But then many Christians turn right around and say, “But in the future, Jesus is going to return to this earth, and slaughter millions of people. There will be the greatest, bloodiest war the world has ever seen. When Jesus returns at the battle of Armageddon, the Valley will be filled with blood up to the horse’s bridle.”

But then many Christians turn right around and say, “But in the future, Jesus is going to return to this earth, and slaughter millions of people. There will be the greatest, bloodiest war the world has ever seen. When Jesus returns at the battle of Armageddon, the Valley will be filled with blood up to the horse’s bridle.”

In this text, Jesus provides a summary of how He reads and understands the Old Testament. This is “The Old Testament according to Jesus.” And according to Jesus, the Bible is filled with violent bloodshed.

In this text, Jesus provides a summary of how He reads and understands the Old Testament. This is “The Old Testament according to Jesus.” And according to Jesus, the Bible is filled with violent bloodshed.

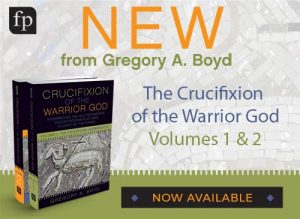

In one of his recent email newsletters (

In one of his recent email newsletters (

“But” (as my wife pointed out to me once), “What about God’s deal with the devil at the beginning of the book? Didn’t God allow Satan to do all these bad things to Job? How is this not divine violence?” Excellent point, Wendy! My answer is that this proves that the book of Job is actually about the satanic activity of accusing and blaming others in the name of God. Satan is there in the beginning as the accuser, and the satanic presence is seen throughout the book as everyone is accusing Job, and Job is accusing God.

“But” (as my wife pointed out to me once), “What about God’s deal with the devil at the beginning of the book? Didn’t God allow Satan to do all these bad things to Job? How is this not divine violence?” Excellent point, Wendy! My answer is that this proves that the book of Job is actually about the satanic activity of accusing and blaming others in the name of God. Satan is there in the beginning as the accuser, and the satanic presence is seen throughout the book as everyone is accusing Job, and Job is accusing God. I had a very similar conversation with Greg at the ReKnew conference, in which he stated that he also leaves natural disasters completely unexplained. He says, and I agree, that there are too many variables to determine the cause of any natural disaster. The only exception, Greg says, are the natural disasters found in the Bible. The Bible claims that these (in some way) came from God, and so therefore, they did. Call it Satan, the destroyer, or God withdrawing, these, and only these, natural disasters have some sort of divine origin. For many reasons, I find this explanation highly troubling, and extremely unhelpful. After all, if the CWG thesis helps us understand the Bible but not life, then it is not helpful and cannot be accepted.

I had a very similar conversation with Greg at the ReKnew conference, in which he stated that he also leaves natural disasters completely unexplained. He says, and I agree, that there are too many variables to determine the cause of any natural disaster. The only exception, Greg says, are the natural disasters found in the Bible. The Bible claims that these (in some way) came from God, and so therefore, they did. Call it Satan, the destroyer, or God withdrawing, these, and only these, natural disasters have some sort of divine origin. For many reasons, I find this explanation highly troubling, and extremely unhelpful. After all, if the CWG thesis helps us understand the Bible but not life, then it is not helpful and cannot be accepted. Frankly, most people, myself included, would rather have the pain and punishment come directly from God. If God is going to let satan kill people, God should have the respect for humanity to just do it Himself. If Greg’s view of God is correct, then I say this to God, “Hey God, man up. Don’t send a hit man to do your dirty work.”

Frankly, most people, myself included, would rather have the pain and punishment come directly from God. If God is going to let satan kill people, God should have the respect for humanity to just do it Himself. If Greg’s view of God is correct, then I say this to God, “Hey God, man up. Don’t send a hit man to do your dirty work.”  Anyway, the death of Jesus is the center of Scripture and theology, and I base everything I think and teach on what Jesus accomplished on the cross. Or at least, I try to. I believe every word of Scripture; I just believe some of these words differently than Greg does. This doesn’t mean I’m wrong, or that he is. It just means there is room for further discussion and humble learning. If Greg decides to continue this conversation, I promise not to mention Girard.

Anyway, the death of Jesus is the center of Scripture and theology, and I base everything I think and teach on what Jesus accomplished on the cross. Or at least, I try to. I believe every word of Scripture; I just believe some of these words differently than Greg does. This doesn’t mean I’m wrong, or that he is. It just means there is room for further discussion and humble learning. If Greg decides to continue this conversation, I promise not to mention Girard.