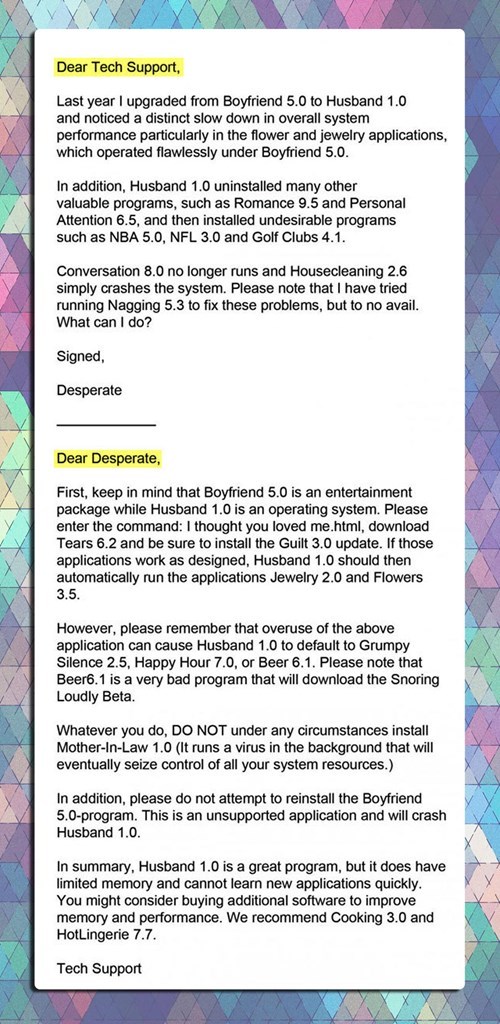

When I showed this image to my wife, she laughed.

She laughed a little too much… It was hard for her to stop laughing…

Hmmm…

Consider sharing it with others below:

Liberating you from bad ideas about God

Stop relying on pastors and Bible teachers to tell you what the Bible means.

Read this book and learn to study the Bible for yourself. Available now on Amazon.

The book discussion questions with each chapter to make it perfect for a home study group. There is also a LONG appendix on how to understand the violent passages in Scripture.

When I showed this image to my wife, she laughed.

She laughed a little too much… It was hard for her to stop laughing…

Hmmm…

Consider sharing it with others below:

You don’t have to believe the entire gospel to receive eternal life. And even if you believed in the gospel, you might not be saved.

Do such statements shock you?

They should—especially if you hold to one of the traditional (yet not so biblical) definitions for the words “gospel” and “saved.”

When most people today hear the sentence “You must believe the gospel to be saved” what actually goes through their mind is this: “Here are the things you must believe in order to go to heaven when you die” (And of course, everyone has a different idea about what we must believe).

So people are often shocked to learn that the biblical word “gospel” (Gk., euangelion) means way more than what a person need to believe to receive eternal life. Similarly, the biblical word for “salvation” (Gk., sōteria) has very little to do with going to heaven when you die.

To see what each word means, we will look at the word “gospel” in the next couple posts, and the word “salvation” in a few posts after that.

The word “gospel” means “good news.”

And although “gospel” almost universally today refers to good news about forgiveness of sin and the offer of eternal life through Jesus Christ, the word itself carries no such connotations.

In ancient and biblical times, the word is often used regarding things like children who recovered from sickness, a battle which was won, or a successful trading voyage (See my article on the gospel where I document this in more detail).

Just as the words “good news” can refer to almost any sort of happy event or positive outcome today, so also, the words “good news” or “gospel” could refer to almost anything good in biblical times as well.

In the New Testament itself, though, the phrase “good news” or “gospel” has a more focused meaning.

Though it can sometimes refer simply to an encouraging message (1 Thess 3:6), and Jesus often used the term to describe the coming of the Kingdom of God (cf. Matt 4:23; 9:35), Paul is the one who used the word in his writings, and he uses the word most often in reference to describe the complete chain of events regarding what God has done for sinful humanity through Jesus Christ to provide eternal life for them.

Though it can sometimes refer simply to an encouraging message (1 Thess 3:6), and Jesus often used the term to describe the coming of the Kingdom of God (cf. Matt 4:23; 9:35), Paul is the one who used the word in his writings, and he uses the word most often in reference to describe the complete chain of events regarding what God has done for sinful humanity through Jesus Christ to provide eternal life for them.

And when I write “the complete chain of events” I mean the complete chain, beginning with God eternal love for humanity, including the creation of mankind and their subsequent fall, and going through God’s calling of Israel, His work through them during their checkered history, the birth, life, ministry, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus, and looking forward to the return of Jesus and the new heavens, the new earth, and our eternal existence with God. The biblical “gospel” includes all of this. Every bit.

While the term gospel is a non-technical term for any good news, the NT usage seems to define it as good news for everybody, whether Jew or Gentile, believer or unbeliever, regarding the benefits and blessings which come to us from the person and work of Jesus Christ. It includes everything from “the eschatological expectation, the proclamation of the [kingdom of God] … the introduction of the Gentiles into salvation history, [and] the rejection of the ordinary religion of cult and Law.” This gospel contains everything related to the person and work of Jesus Christ, including all of the events leading up to His birth, and all the ramifications from Christ’s life, death, and resurrection for unbelievers and believers. (see p. 50 of my article on the gospel).

So what is the gospel? It is everything about Jesus.

So do you see why you don’t have to believe “the gospel” to receive eternal life? The reason is because you cannot believe everything about Jesus. It’s impossible to know everything about Jesus, let alone believe everything (we will talk about Mark 1:15 in a later post). To receive eternal life, you simply believe in Jesus for it (John 3:16; 5:24; 6:47, etc.). This is a truth within the gospel, but is not itself “the gospel.”

Want to learn more about the gospel? Take my new course, "The Gospel According to Scripture."

Want to learn more about the gospel? Take my new course, "The Gospel According to Scripture."

The entire course is free for those who join my online Discipleship group here on RedeemingGod.com. I can't wait to see you inside the course!

If we define faith as “confidence” or “conviction” based on the evidence presented, and once we recognize that there is no such thing as “degrees of faith,” then this leads to the truth that faith is not a work.

If we do not choose to believe something, then it cannot be said in that faith is meritorious. That is, faith does not contribute in any way to our goodness before God.

Calvinists often argue that if man “contributes” faith to the process of salvation, then man has done a good work to earn that salvation, which therefore makes salvation not a gracious gift of God but a transaction between God and man.

But if faith is not something we choose, but is rather something that happens to us when we are persuaded or convinced that something is true, then we cannot say in any way that faith is a work. Besides, Paul pretty clearly contrasts faith and works in Romans 4:5.

Yet despite the fact that faith is not something we choose but is that which happens to us based on the evidence presented, we must not go to the other extreme and say that faith is a gift.

Faith is not a gift. Though there is a spiritual gift of faith (1 Cor 12:9), this is not to be confused with the faith that leads to eternal life (John 3:16; 5:24; 6:47, etc.).

And though some claim that the “gift” which Paul refers to in Ephesians 2:8-9 is faith, the Greek word “that” (“that not of yourselves, it is the gift of God) is neuter and the Greek word for “faith” is feminine, which means the gift of God is not faith, but rather the entire “salvation package” which originated with God (i.e, “by grace you have been saved”). See the excellent article by Rene Lopez on whether or not faith is a gift.

What then is biblical faith (or belief)? In the end, we can do no better at defining faith than does the author of Hebrews. He writes: “Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (Heb 11:1).

To expand on this a bit, we could say that faith substantiates, or sees as reality, that which we previously only hoped to be true; it is the evidence, conviction, or confidence in things we cannot see. Certainly, some things we believe in can be seen, but the great faith described in the rest of Hebrews 11 is the faith that is confident in God’s promises based on what is known about God’s character and God’s Word.

Faith is the confidence or conviction that something is true based on the evidence presented.

Faith is seeing what is true based on what we know to be true.

Yesterday we defined faith as confidence or conviction. One of the problem people sometimes have with this sort of definition, however, is that we think that there are degrees of faith, or (to put it another way), faith is on a sliding scale, where one end is “wishful-hope-so-thinking” and on the other end is “absolute certainty.”

Though lots of people like to talk about “degrees of faith” this is not a proper way of thinking about biblical faith.

Faith is more like a light switch (and not a dimmer switch!). Just as a light is either on or off, so also, you either believe something or you don’t. If you are not sure whether or not you believe something, then you don’t believe it. If you are partially convinced, but not yet fully convinced, then you do not believe.

Though Scripture does talk about “little faith” and “great faith” (e.g., Matt 8:10, 26), this is not a reference to the degree of faith someone has, but to the difficulty of the truth believed. Some things are easier to believe than others, and so when someone does not even believe the simple and obvious things, they have little faith, whereas, when someone believes things that are difficult to believe, they have great faith (See my article, “Now That’s Faith” for more.)

Though Scripture does talk about “little faith” and “great faith” (e.g., Matt 8:10, 26), this is not a reference to the degree of faith someone has, but to the difficulty of the truth believed. Some things are easier to believe than others, and so when someone does not even believe the simple and obvious things, they have little faith, whereas, when someone believes things that are difficult to believe, they have great faith (See my article, “Now That’s Faith” for more.)

What all of this means is that we cannot exactly “choose” to believe something. Belief, or faith, is not a decision we make. Faith is something that happens to us when presented with convincing and persuasive evidence.

Sometimes we might not be able to believe something until we see it with our own eyes. Other times, we might come to faith through reason, logic, and the weight of argumentation. Occasionally, we even come to believe something despite our desire not to believe it.

For example, if a father was told that his son was a mass-murderer, the father might not want to believe it, and would not believe it. But if the father sat through the trial of his son, and saw the weight of the evidence, and maybe even heard the confession of his son to his crimes, the father would be forced to believe what he did not want to believe. The father did not choose to believe, but was persuaded or convinced by the evidence presented, and came to believe something he did not wish to be true.

So while facts, logic, and reason can lead to faith, so also can experience, relationships, and revelation. Even hope and trust, which are not themselves faith, can be transformed into faith.

Faith itself can lead to faith, for once we believe some things about God, it becomes easier to believe other things. Divine revelation itself can lead us to believe things about God, ourselves, and eternity which we may not have believed otherwise (Rom 10:17).

Defining “faith” (Gk., pistis) and the verb “believe” (Gk., pisteuō) is a bit like trying to define love. We can look up the words in Greek and Hebrew dictionaries and compare how the words were used in various ancient contexts, but when it comes down to how the word is used in real life, the way the word is used today bears little resemblance to the way the word was used in biblical times.

With love, we go through our days talking about how we love football, love pizza, love our cars, and love our spouse, and then we read in Scripture about how we are to love God and love one another, and although we know there is a difference between the various forms of love, we don’t really think about it too much or understand the ways that biblical “love” might be different than our modern use of the word.

It is similar with “faith” and “believe.” Often, when people use these words today, it means little more than “hope.”

Though someone might say they believe the Bears will win the Super Bowl this year, they know, as does everyone else, that their faith is little more than hope. You even sometimes hear people say “I believe I will win the lottery!”

In this case, the word “believe” does not even rise to the level of hope, but is nothing more than wishful thinking.

Sometimes when “faith” is used today, it means “trust.” Banks talk about the “full faith and credit” of the United States Government in insuring our deposits, meaning that we trust that if the bank loses our money, the government will give it to us.

Or as another example, you may have heard the story about a man who crossed Niagara Falls while pushing a wheelbarrow, and then asked the watching crowd if they believed he could do this same feat with a person in the wheelbarrow. They all enthusiastically shouted “Yes!” but when he asked for volunteers, nobody came forward. This illustration is sometimes used to suggest that faith without follow-through is not really faith; but what it really proves is that there is a difference between faith and trust.

In light of this, people get confused—and rightfully so—when they read about faith and belief in the Bible. They are not sure whether they should understand faith to be more like hope, wishful thinking, trust, or maybe something else.

So when it comes to the biblical definition of faith, it is probably best to think about faith (and the verb “believe”) as a confidence, persuasion, or conviction that something is true. While it need not rise to the level of certainty—for we have all know that beliefs can change when we are presented with new evidence—faith is being fully persuaded by the evidence we now have.

We will talk a bit more about what faith is and what faith isn’t in the days ahead, but for now, what do you think of defining faith as “confidence”?

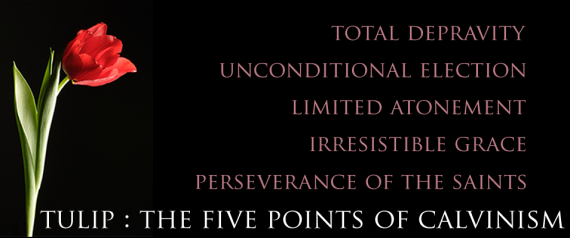

It is important to know before embarking on a serious study of Calvinism that Calvinism goes by various names.

Sometimes it is called “The Doctrines of Grace” and other times it is referred to as “Reformed Theology.”

This sort of terminology reveals, in my opinion, the pride and arrogance of some Calvinists,for despite the claims of some Calvinists, many people who are not Calvinists still believe in grace, and not all the Reformers were Calvinistic.

Calvinists also like to claim that Calvinism is equivalent to the gospel, and that there is no such thing as biblical Christianity that is not Calvinistic. All I can do is shake my head at such statements…

Anyway, you should know that if you hear people talking about “the Doctrines of Grace” or “Reformed Theology” they are probably referring to Calvinism.

Nevertheless, I believe it is inaccurate for Calvinists to attempt to appropriate the words “grace” and “reformed” for their own system of theology, especially when, in my opinion, many Calvinists know less of grace than their opponents, and numerous others have stopped seeking further theological reformation.

Though I am not a Calvinist, I hold to radical, outrageous, scandalous grace (a grace which is more gracious than the grace of many Calvinists), and I believe that as fallen and sinful human beings, we should always be about the work of reforming ourselves and our theology and never consider ourselves fully reformed.

So despite the tendency of some to refer to Calvinism as “The Doctrines of Grace” or “Reformed Theology,” I reject both titles as misleading and inaccurate.

In the posts that follow I hope to show that while I am not a Calvinist, I stand fully within the Reformation emphases of grace, faith, Jesus Christ, Scripture, and the glory of God.

Though I have sometimes joked that I am a two-and-a-half point Calvinist, it is only because I hold to half of each point of Calvinism, which is really no Calvinism at all.

I believe in depravity, but not total depravity.

I believe in election, but not unconditional election.

I believe in the atonement, but not limited atonement.

I believe in grace, but not irresistible grace.

I believe we are saints, but not in the perseverance of the saints.

Be careful not to quote too much Scripture to an atheist… because he or she may start quoting Scripture right back! There are a lot of verses in the Bible that seem downright, well, anti-biblical. Or at least anti-christ.

You know… verses about killing babies, marrying girls you raped, and slaughtering all your enemies (including their cows and sheep).

Would Jesus command such things? I don’t think so…

Yesterday I tried to summarize Calvinism with my own words. This is always a dangerous task. In the book I am currently writing on Calvinism, I will always seek to let Calvinists present their views in their own words.

Yesterday I tried to summarize Calvinism with my own words. This is always a dangerous task. In the book I am currently writing on Calvinism, I will always seek to let Calvinists present their views in their own words.

So, as a way of appeasing any critics of my personal summary of five-point Calvinism yesterday, I thought I would post a Calvinistic summary today.

Here is what David N. Steele, Curtis C. Thomas, and S. Lance Quinn have written in their book The Five Points of Calvinism:

Because of the Fall, man is unable of himself to savingly believe the gospel. The sinner is dead, blind, and deaf to the things of God; his heart is deceitful and desperately corrupt. His will is not free; it is in bondage to his evil nature. Therefore, he will not—indeed, he cannot—choose good over evil in the spiritual realm. Consequently, it takes much more than the Spirit’s assistance to bring a sinner to Christ. It takes regeneration, by which the Spirit makes the sinner alive and gives him a new nature. Faith is not something man contributes to salvation, but is itself a part of God’s gift of salvation. It is God’s gift to the sinner, not the sinner’s gift to God.

God’s choice of certain individuals for salvation before the foundation of the world rested solely on His own sovereign will. His choice of particular sinners was not based on any forseen response or obedience on their part, such as faith, repentance, etc. On the contrary, God gives faith and repentance to each individual whom He selected. These acts are the result, not the cause, of God’s choice. Election, therefore, was not determined by, or conditioned upon, any virtuous quality or act forseen in man. Those whom God sovereignly elected He brings through the power of the Spirit to a willing acceptance of Christ. Thus, God’s choice of the sinner, not the sinner’s choice of Christ, is the ultimate cause of salvation.

Christ’s redeeming work was intended to save the elect only and actually secured salvation for them. His death was a substiutionary endurance of the penalty of sin in the place of certain specified sinners. In addition to putting away the sins of His people, Christ’s redemption secured everything necessary for their salvation, including faith, which unites them to Him. The gift of faith is infallibly applied by the Spirit to all for whom Christ died, thereby guaranteeing their salvation.

In addition to the outward general call to salvation, which is made to everyone who hears the gospel, the Holy Spirit extends to the elect a special inward call that inevitably brings them to salvation. The external call (which is made to all without distinction) can be, and often is, rejected. However, the internal call (which is made only to the elect) cannot be rejected; it always results in conversion. By means of this special call, the Spirit irresistibly draws sinners to Christ. He is not limited to His work of applying salvation by man’s will, nor is He dependent upon man’s cooperation for success. The Spirit graciously causes the elect sinner to cooperate, to believe, to repent, to come freely and willingly to Christ. God’s grace, therefore, is invincible; it never fails to result in the salvation of those to whom it is extended.

All who are chosen by God, redeemed by Christ, and given faith by the Spirit, are eternally saved. They are kept in faith by the power of almighty God, and thus persevere to the end (The Five Points of Calvinism, pp 5-8).

Other Calvinists might summarize the Five Points of Calvinism somewhat differently, but this summary from three leading Calvinists is fairly typical.

However, here is one super succinct summary, from leading Calvinistic pastor and author, John MacArthur:

(1) Sinners are utterly helpless to redeem themselves or to contribute anything meritorious toward their own salvation (Rom. 8:7-8). (2) God is sovereign in the exercise of His saving will (Eph 1:4-5). (3) Christ died as a substitute who bore the full weight of God’s wrath on behalf of His people, and His atoning work alone is efficacious for their salvation (Isa 53:5). (4) God’s saving purpose cannot be thwarted (John 6:37), meaning none of Christ’s true sheep will ever be lost (John 10:27-29). That is because (5) God assures the perseverance of His elect (Jude 24; Phil 1:6; 1 Peter 1:5).

As you read over these summaries, you may not see anything that stands out as overly objectionable. You might think that based on the statements above, Calvinism sounds pretty reasonable, and quite biblical.

Yes, that is one of the strengths of Calvinism.

Yet as we look at each of the Five Points in more detail in subsequent posts, we will make room for other Calvinistic voices to be heard as well, and as we look at the biblical passages they use to defend their theology, we will see that Calvinism may not be as reasonable or biblical as it first appears.

If you are a Calvinist, do you think the summaries above are fair? What would you clarify? If you are not a Calvinist, or are just learning about Calvinism, what are your thoughts so far?

Some say that John Calvin was not a Calvinist.

In some regards, this is probably true. There are one or two points of Calvinism which John Calvin is less than clear about in his writings. In some places, he seems to say one thing, and in other places, he says the opposite. This is not too surprising, especially for someone who wrote as voluminously as did John Calvin.

But the real reason we can say that John Calvin was truly not a Calvinist is because he himself did not develop the system of theology which bears his name.

Several years after John Calvin died in 1564 (click here to see a brief history of John Calvin), a man named Jacobus Arminius traveled to Geneva to study under Theodore Beza, who was Calvin’s successor.

Several years after John Calvin died in 1564 (click here to see a brief history of John Calvin), a man named Jacobus Arminius traveled to Geneva to study under Theodore Beza, who was Calvin’s successor.

After Arminius completed his studies in 1587, he moved to Amsterdam to pastor a church there. As he as preaching through Romans in the years that followed, he developed several points of disagreement with the theology of John Calvin. In fact, it was actually in seeking to defend the teachings of Calvin against some detractors that led Arminius to have doubts of his own. So just as Luther and Calvin had sought to reform the church of their day, Arminius sought to reform Calvinism.

After Jacobus Arminius died in 1609, some of his followers put together a document called “The Five Articles of Remonstrance.” In much the same way that Martin Luther had posted his 95 Theses on the church door in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517, for the purpose of stating his objections to the abuses he saw within the Roman Catholic Church and inviting church leaders to gather and discuss these items, so also, the Five Articles of Remonstrance were an invitation by the followers of Arminius to the followers of Calvin to gather for the purpose of discussing these issues.

Instead, the followers of John Calvin met in Dordrecht, Netherlands from 1618 to 1619 and crafted what has become known as the Canons of Dort. This consisted of a point-by-point refutation and condemnation of the Five Articles of Remonstrance.

As such, there were five main points to this second document. It is these five main points in the Canons of Dort that have become known as “Calvinism.”

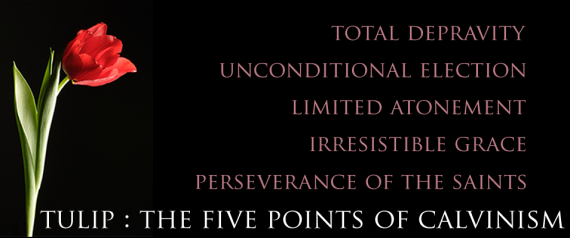

The five Canons of Dort are often summarized today by the acrostic TULIP:

Total Depravity

Unconditional Election

Limited Atonement

Irresistible Grace

Perseverance of the Saints

TULIP Calvinism begins with the idea that mankind is completely sinful and cannot do anything to contribute to his salvation (Total Depravity).

As a result, we are totally dependent upon God to initiate salvation for us, which He did in eternity past by choosing to save some, without any condition or merit on the part of those whom He chose (Unconditional Election).

In order to accomplish this salvation of those whom He had previously chosen, God sent Jesus to die specifically and only for the sins of those whom He had chosen so that they might have eternal life (Limited Atonement).

Those whom God has chosen, and for whom Christ died, will be irresistibly drawn by God’s grace into God’s family (Irresistible Grace).

Since God’s will cannot be thwarted, none whom God has chosen, for whom Christ died, and whom were drawn and transformed by God’s grace, can ultimately be lost. They will all be glorified. Due to this gift of grace in their life, all who are delivered by God’s grace in this fashion will give evidence to it by living a life of perseverance in faith and good works (Perseverance of the Saints).

The so-called sixth point of Calvinism, which of course is not mentioned in the five points above, but which undergirds them all, is the Sovereignty of God. One can see that God’s complete control over all things is behind each of the five points.

God must be in control, and God must accomplish everything, from first to last, if humans are to have any hope of salvation, and if God is to be certain of defeating sin, death, and the devil in the ultimate end.

God must be in control, and God must accomplish everything, from first to last, if humans are to have any hope of salvation, and if God is to be certain of defeating sin, death, and the devil in the ultimate end.

Not all Calvinists will be happy with the brief summary above. I have tried to state the view as succinctly and clearly as I know how, and in fact, I tried to write that summary in a way that almost nobody could disagree with it—not even most non-Calvinists.

If you are trying to figure out what Calvinism is all about, it is likely that as you read through that brief description of the five points of Calvinism, you though, “Yeah? So? That’s what I believe. That’s what the Bible teaches, isn’t it?” Yes, well, that is what this series of posts on Calvinism will seek to determine.

Nevertheless, for those Calvinists who feel I did not properly explain Calvinism, tomorrow I will post some summaries of Calvinism from leading Calvinists. (This will be a common practice in my series on Calvinism … to allow Calvinists to explain their views in their own words. I hope any Calvinists reading this will allow me to do the same with my own views.)

John Calvin was born in France in 1509 and was raised as a Roman Catholic. His father initially intended John to enter the priesthood, but realized later in life that there was more money to be made in law, and so in 1525, sent John to become a lawyer.

It was during this time that the ripple effects of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses (published in 1517) were beginning to be seen throughout all of Europe. In 1533 John Calvin experienced his conversion, and later that year, one of John Calvin’s close friends, Nicolas Cop, publicly sided with the Reformers in calling for changes in the Roman Catholic Church. As a result, Cop was condemned by the Catholic Church as a heretic, and was forced to flee for his life. Calvin was also implicated in the condemnation and was also forced to go into hiding.

In 1536, Calvin published his first edition of the Institutes of the Christian Religion, which was initially intended to be a short explanation and defense of the teachings and ideas of the Reformers. The book went through numerous subsequent expansions over the course of John Calvin’s life.

A short time later, during one of his travels, John Calvin traveled to Geneva, and a man there named William Farel convinced John to stay and help reform the church in Geneva. He agreed, and in 1537 he was selected to be a pastor of the church.

However, by the end of the year, the church council forced Calvin to resign his position and leave Geneva because he wanted to force church members to sign his doctrinal statement and articles of church organization (which few people wanted to do), and because he refused to serve communion with unleavened bread on Easter Sunday.

Calvin traveled to Strasbourg, which was a city of refuge for Reformed people, and over the course of the next three years, preached and taught in three different churches. He also worked on an updated version of the Institutes, and published his Commentary on Romans.

During the time, the church in Geneva dwindled in size, and was facing pressure by the Roman Catholic Church to return to Catholicism. By way of response, the Genevan church called upon Calvin to write a letter in their defense, which he gladly did. They were so pleased with his letter, they asked him to return to Geneva and take up the pastoral position once again.

During the time, the church in Geneva dwindled in size, and was facing pressure by the Roman Catholic Church to return to Catholicism. By way of response, the Genevan church called upon Calvin to write a letter in their defense, which he gladly did. They were so pleased with his letter, they asked him to return to Geneva and take up the pastoral position once again.

In 1541, Calvin returned to Geneva under the condition that the church accept and adopt his proposed reforms. They agreed. Calvin ministered in Geneva for the rest of his life, until he died in 1564. The first few years of his ministry were busy and productive. He preached an average of five sermons a week, and wrote numerous books, tracts, as a well as a set of commentaries on almost every book of the Bible.

However, his ministry in Geneva was not without opposition.

Not all agreed with Calvin’s teaching and theology, and many accused Calvin of teaching false doctrine. From 1546 to 1553, Calvin’s power and influence steadily waned. There were frequent attempts by both sides of the debate to undermine, arrest, and even kill members of the other party.

As one example, a man named Jacques Gruet was arrested and, under torture, confessed to writing an anonymous letter in opposition to the church leaders. Gruet was beheaded in July of 1547.

Eventually, the opposition to Calvin became so fierce, that in July of 1553, Calvin offered to resign his position a second time. His request was refused, because those who opposed him knew that an uprising and church split would likely occur if they accepted Calvin’s resignation.

One month later, in August of 1553, all of Calvin’s fortunes changed when a man by the name of Michael Servetus arrived in Geneva. Servetus also was a Protestant Reformer, but had been condemned as a heretic by both Catholic and Protestant church leaders for his writings against the Trinity and infant baptism.

Though Calvin and Servetus had debated these issues by letter for many years, they had never met in person, yet when Servetus stopped in Geneva on his way to Italy, he was recognized and arrested. A trial ensued, in which Servetus was once again condemned as a heretic, and on October 27, 1553, was burned at the stake on top of a pile of his own books.

As a result of his involvement in the arrest, trial, and execution of Servetus, John Calvin was acclaimed across all of Europe as a defender of Christianity.

Over the next two years, his power and fame grew as never before, and in 1555, all who had previously opposed John Calvin either fled Geneva or were rounded up and executed.

Over the next two years, his power and fame grew as never before, and in 1555, all who had previously opposed John Calvin either fled Geneva or were rounded up and executed.

From 1555 until his death in 1564, Calvin’s position, power, and reputation went almost completely uncontested. He did experience some controversy with Martin Luther over the issue of consubstantiation, but even this controversy with Martin Luther—the “father” of the Reformation itself—only solidified Calvin’s position of prominence in the minds of many.

During these final years, he continued to write, preach, and teach, and he also founded several schools, including Calvin College (Collège Calvin) in Geneva, Switzerland in 1559.

In 1558, he finished his final edition of the Institutes, and he preached his last sermon on February 6, 1564, before dying on May 27, 1564.

After his death, Theodore Beza took over Calvin’s position in Geneva and helped carry on his work and ideas.

This is obviously a very short and summarized history of John Calvin’s life. For those of you who have studied John Calvin, do you have anything to add? For those who didn’t know much about Calvin, what are your initial impressions from this brief account? Let us know in the comments below.