Kregel Publications recently sent me a review copy of Philip Wesley Comfort’s new study resource, A Commentary on the Manuscripts and Text of the New Testament (Get it on Amazon or at CBD.

Kregel Publications recently sent me a review copy of Philip Wesley Comfort’s new study resource, A Commentary on the Manuscripts and Text of the New Testament (Get it on Amazon or at CBD.

If you are relatively familiar with how pastors and theologians study the Bible, you probably know about commentaries on books of the Bible. Those commentaries provide insights and suggestions on the text of Scripture to help the Bible student know what the texts means, how to teach it, and how to apply it to our lives.

That is NOT what this commentary by Comfort is about.

This book is a commentary on the manuscripts of the New Testament.

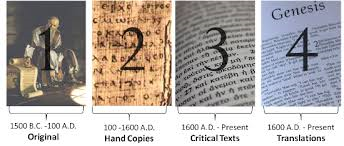

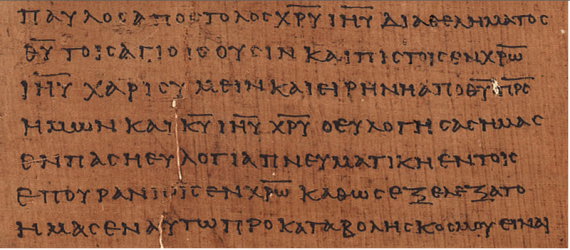

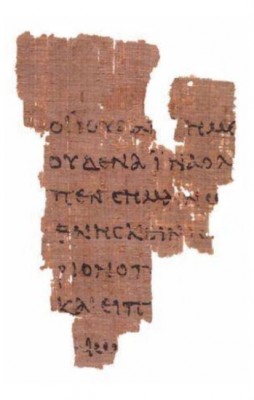

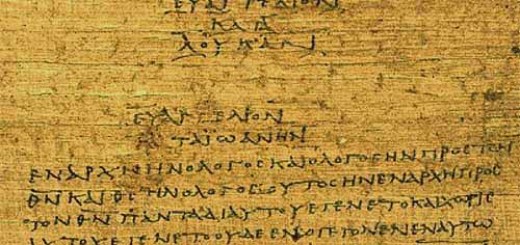

In case you did not know it, we do not have the original manuscripts (called the autographs) of the New Testament books that were written by Matthew, Luke, Paul, John, etc. We only have hand-written copies. But we have hundreds (and in some cases, thousands) of copies.

From one perspective, this is a good thing, for the textual evidence of the New Testament is much stronger than any other ancient Greek piece of literature. No other piece of ancient Greek literature has as much textual support as does the New Testament.

But here’s the problem: Not all of these copies of the various books of the New Testament agree with each other. There are textual variants in the copies.

So the task of the New Testament Greek scholar is to look at the various copies of the New Testament, and try to decide which of the variant readings most likely reflects what Matthew, or Luke, or Paul actually wrote. Then, these “probable” readings get compiled together into our Greek New Testaments today, and it is from these that our English translations are made.

Anyway, this new book by Philip Wesley Comfort looks at a large number of the variant readings from the textual families, and briefly explains what the variations are, and what Comfort thinks is the best reading for a particular variant.

Comfort’s book, of course, is not the only one like it. Nearly all Greek New Testaments have a summarized version of this sort of textual commentary in the bottom portion of every page (it is called the Critical Apparatus). In my own study and research, I use two or three other similar tools as well. One tool I have commonly used is very similar to the one Comfort has compiled, and it is A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament by Bruce Metzger. So, since I am familiar with that tool, I decided that in the process of reviewing Comfort’s Commentary, I would compare the two.

After spending several hours comparing the two commentaries, and studying their own explanations of numerous variants, here are my observations about the two books:

There are a lot of variants

I always knew there were a lot of variants in the Greek manuscripts, but I had forgotten just how many there were. It seems almost every paragraph in the New Testament has a couple. Nevertheless, I sort of assumed that most scholars sort of agreed on what the “major” variants were.

I always knew there were a lot of variants in the Greek manuscripts, but I had forgotten just how many there were. It seems almost every paragraph in the New Testament has a couple. Nevertheless, I sort of assumed that most scholars sort of agreed on what the “major” variants were.

But as I compared Comfort with Metzger, I realized that there were lots of variants discussed by Metzger which Comfort ignored, and lots of variants discussed by Comfort which Metzger ignored.

Metzger’s volume discussed fewer variants than Comfort, but his discussions are longer and provide more detail about why he chose the variant he did. Comfort, on the other hand, discusses more variants, but his discussions are much shorter, usually only a sentence or two. For that reason alone, you almost need both books.

Scholars Don’t Agree

The second thing I noticed is that while Comfort and Metzger agreed a lot of the time on which textual variant is preferred, they disagreed a lot as well. And on some major verses!

Take Matthew 12:47 for example. The issue here is whether or not to include the entire verse. Metzger says that it should be included “with brackets” indicating that there is some doubt about whether it is original, whereas Comfort says the best reading is just to omit the verse altogether.

There were hundreds of similar such differences of opinion.

Scholarly Squabbles are Funny

Finally, I enjoyed seeing why and how Comfort defended some of his choices. I laughed a little bit when, on page 23, Philip Comfort wrote this:

… Not only do we need to know the original texts, we also need to know the tendencies of the scribes who produced the texts

You see? Comfort is saying that the reasons he chose the textual variants he did, is because he tried to understand the tendencies of the scribe who made the copies! Therefore, Comfort’s choices are better than those who look only at the texts themselves …

When I read that, I thought to myself,

It used to be that you could trump somebody’s exegesis of the text by saying, “Well, although the English says X, in the Greek it says Y …” But then it began to be that this was no longer good enough, for you had to go back further and say, “Well, although the Greek text you are using says Y, the variant reading from Papyrus 46 says Z, and it is preferable for reasons A, B, and C. But now, Comfort is saying that it is not enough to just know what Papyrus 46 says and why it is preferable for reasons A, B, and C. No, now you also have to understand the tendencies of the guy who was making the copy of the text!

So what’s next? Maybe next we will need to know the lighting of the room in which the guy was sitting which caused him not to see the text very clearly, and how he had a fight with his wife that morning, so his mind wasn’t properly focused on his work, and how his ink well had just run dry so he had to get up and get more ink, thus interrupting his attention, and just at that moment, and cat walked sat on his desk (as cats like to do), smudging the work which he had completed, which explains why there is this textual variant in Matthew 12:47.

I know, I know. That will never happen. But it made me laugh at how smart we modern people think we are, speaking so confidently about “what the text says,” when we base our opinions off of some dubious rules for “the best reading of the text” (which nobody agrees on anyway, and even if they do agree on the rules, nobody comes to consensus on how to consistently apply them to the textual variants, See p. 30). When Comfort stated that he is making his decisions based on his research into the tendencies of the scribes who produced the texts, it reminded me of the Parable of the Oyster and Ballerinas.

I am not criticizing the book. It is an excellent tool. And I am definitely not criticizing textual criticism. We must be thankful for the work of the scholars who have spent their life on this task, for it is only because of them that we have the Bibles we have today.

All I am saying is that no matter how much Greek you know, there will always be people who know more than you, and will say that your theology is wrong because you don’t know enough. Even world-class Greek scholars like Comfort “one up” other world-class Greek scholars by saying that the others didn’t understand the tendencies of the scribes who copied the texts.

My Complaint With Textual Criticism

I love studying the Greek (and Hebrew) texts of the Bible. However, I am learning that as important as Greek and Hebrew textual study is, we must not think that the critical study of the text is going to solve all our exegetical and theological dilemmas. It won’t.

My biggest problem with textual criticism is with the canons (or rules) of Textual Criticism. Comfort lists them on p. 30, and while I most of them are good rules (I have serious misgivings about several), the application of these rules is highly subjective, as Comfort himself points out. Even if you get two Greek scholars to agree on the rules, they still will not agree on how these rules are to be applied to a particular variant. The perfect example is how often Comfort disagrees with Metzger as pointed out above…

It is this sort of scholarly disagreement that causes some Christians to just throw up their hands and say, “Why bother? If the experts cannot even agree on what words should even be in the text, how can I begin to study the Bible for myself?”

Here is my answer: Let the scholars have their fun. For it is fun for them. And then, you and I, let’s just read the text that we have, for what else can we do?

If you want to know what the Bible says, just study it, read it, pray over it, and ask God to guide you by the Holy Spirit. Most of all, remember always that you have the mind of Christ (1 Cor 2:16), which is way better than knowing whether or not Matthew 12:47 should actually be in your Bible or not.

Oh, and here is the #1 rule of Bible interpretation: Stay humble in your conclusions.

For all the mentions of human violence, references to divine violence appear almost twice as often.

For all the mentions of human violence, references to divine violence appear almost twice as often. Though innocent of any wrongdoing, God, in Jesus, let us blame Him for every wrongdoing.

Though innocent of any wrongdoing, God, in Jesus, let us blame Him for every wrongdoing.

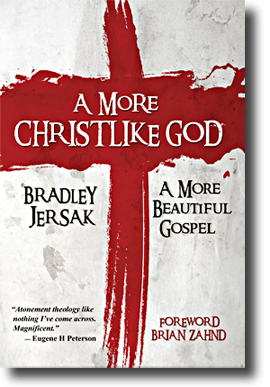

One of the key sections of A More Christlike God is where Brad Jersak discusses the all-important issue of “the wrath of God.” This idea is found in numerous places in the Bible, and is one of the key issues in this debate about what God is like. Many people assume that the phrase “the wrath of God” indicates that God is angry at us. Jersak presents a compelling case for why this is not a proper understanding of that term. He rightly critiques the idea that “the wrath of God” is God withdrawing His mercy. God never withdraws His mercy. God’s mercy is unfailing and everlasting. His mercy endures forever (Psalm 136).

One of the key sections of A More Christlike God is where Brad Jersak discusses the all-important issue of “the wrath of God.” This idea is found in numerous places in the Bible, and is one of the key issues in this debate about what God is like. Many people assume that the phrase “the wrath of God” indicates that God is angry at us. Jersak presents a compelling case for why this is not a proper understanding of that term. He rightly critiques the idea that “the wrath of God” is God withdrawing His mercy. God never withdraws His mercy. God’s mercy is unfailing and everlasting. His mercy endures forever (Psalm 136).