It is usually quite rare to get excited about a book called Interpreting the General Letters, but either I am super geeky, or this book is simply excellent.

It is usually quite rare to get excited about a book called Interpreting the General Letters, but either I am super geeky, or this book is simply excellent.

It’s probably a bit of both.

I initially thought this book by Herbert W. Bateman IV was going to be just another introduction to the General Letters (Hebrews, James, 1–2 Peter, 1–3 John, Jude), and while it is that, it was so much more. It contained cutting edge research on how the letters were composed, the theology they contain, and how we can understand and teach about these letters today.

Does it still sound boring? Well check this out…

The first chapter is about how the letters were composed. Yeah, I was ready to yawn also. But Bateman shows quite persuasively that the General Letters (and probably the letters of Paul as well?) followed clear letter-writing patterns that were common and well-known in the first century AD. The authors of these letters didn’t just sit down and scribble out a letter. Instead, it appears that they used the guidelines found in professional letter writing manuals that were popular at that time. Yes, that’s right. There were books in use at the time which instructed letter writers in the art of writing letters, even down to suggestions for which words to use in your letter. The letters of 3 John, Jude, and 2 Peter clearly exhibit many of these instructions from these professional letter writing guides, even down to the very words that are used!

Who cares?

Well, if Bateman is right, then what does this say about the inspiration of the Holy Spirit? Does it make you rethink the doctrine of the inspiration of Scripture a bit if, instead of Peter sitting down and just writing a letter because the Holy Spirit inspired certain words for Peter to write, Peter instead got many of these words and ideas from a letter-writing manual?

But it gets worse.

Bateman goes on to show that it is probably unrealistic to think that John, Peter, James, and Jude had special training in the art and skills of rhetorical professional letter writing. And yet since their letters show clear indications that professional letter-writing skills were used, the true historical situation was probably that John, Peter, James, and Jude hired professional letter writers to write the letters for them. And in fact, Bateman goes on to show how there is clear evidence in the General Letters that this is exactly what happened (p. 49ff).

Uh-oh.

Now what just happened to our doctrine of the verbal, plenary inspiration of Scripture? It seems that maybe what John, Peter, James, and Jude did was go to a professionally trained letter writer and provided them with the basic ideas, arguments, and points they wanted to make in their letter, and then let the professional letter writer compose the letter according to the letter writing standards of that day. Now certainly, John, Peter, and Jude would have read the letter before it was sent out, and maybe asked for some word revisions or changes in terminology, but still, if Bateman is right about this, what does this mean for the traditional, evangelical doctrine of the inspiration of Scripture.

Now it is no longer “men of God writing Scripture as they were moved by the Holy Spirit” but rather, something like this: “Men of God having inspired ideas which they provided to a professionally-trained letter writer, who then composed the letter according to standards and guidelines found in a letter-writing manual before getting the approval of the man of God to send the letter out to its intended recipients.”

Yeah, not quite the same thing we hear from our pulpits… but I think Bateman is absolutely right to point some of this things out. It is past time we develop a more robust theology of the inspiration of Scripture.

The rest of the book follows this sort of revolutionary, thought-provoking, theology-shattering approach. The second chapter provides excellent historical and cultural background material to the General Epistles, without which you can never hope to understand the message and meaning of these letters. Chapter 3 provides an overview of the theology of the General letters, and specifically how they fit within the overall goal of God’s plan to reestablish His kingdom rule on earth and redeem a people for Himself to inhabit this kingdom. Again, without this big picture theological perspective, we cannot hope to understand the theology of the General epistles.

The remainder of the book (chapters 4–7) provide a detailed explanation of how to study and teach the texts of the General Epistles, beginning with interpreting them from the Greek and moving on into exegetical outlines and homiletical exposition. This highly scientific approach to the Scripture is the method they teach at Dallas Theological Seminary, and is roughly the same approach I follow in my own research and writing, though in a much abbreviated form. While I appreciate the approach that DTS teaches, it can really only be followed by expert scholars and theologians, and is not feasible for the average student of Scripture, which indicates to me that it is not the only oven the best way of reading and interpreting the biblical text.

Interpreting the General Letters by Bateman is a great introduction to the general letters. Even though the final four chapters will be overwhelming for most readers, the first three chapters contain great help and insight for situating the student of Scripture within the world and mindset of the first century authors and audience.

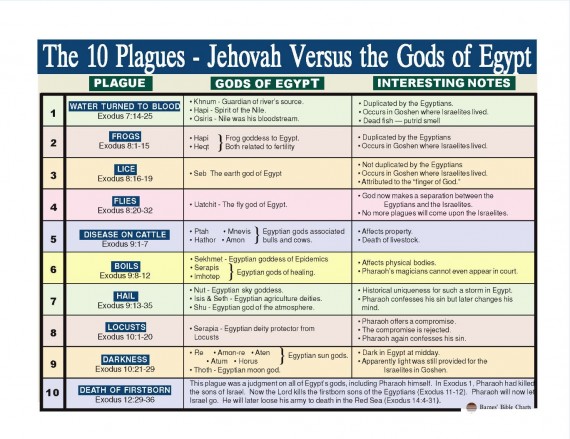

The first is what the writer of the book of Hebrews says about this event in Hebrews 11:28. In that text, the author clearly hesitates from saying that it was God who killed the firstborn sons of Egypt and writes instead about “he who destroyed the firstborn.” The author of Hebrews seems to be saying that it was the destroyer who destroyed the firstborn sons of Egypt, and it was God who kept the destroyer from touching the sons of those families who had the blood of the lamb on their doorpost.

The first is what the writer of the book of Hebrews says about this event in Hebrews 11:28. In that text, the author clearly hesitates from saying that it was God who killed the firstborn sons of Egypt and writes instead about “he who destroyed the firstborn.” The author of Hebrews seems to be saying that it was the destroyer who destroyed the firstborn sons of Egypt, and it was God who kept the destroyer from touching the sons of those families who had the blood of the lamb on their doorpost. Rather than kill the firstborn sons of His enemies, Jesus, the only begotten Son of God, lets Himself be killed by His enemies.

Rather than kill the firstborn sons of His enemies, Jesus, the only begotten Son of God, lets Himself be killed by His enemies.

How can a God who says "Love your enemies" (Matthew 5:44) be the same God who instructs His people in the Old Testament to kill their enemies?

How can a God who says "Love your enemies" (Matthew 5:44) be the same God who instructs His people in the Old Testament to kill their enemies?

For example, Exodus 12:23 says that when God passed over the doors of the houses which had been marked with the blood of the Passover lamb, He would not allow the destroyer to enter into the house to kill the firstborn of that house.

For example, Exodus 12:23 says that when God passed over the doors of the houses which had been marked with the blood of the Passover lamb, He would not allow the destroyer to enter into the house to kill the firstborn of that house.

I want to say several things in this post. Here they are in summary:

I want to say several things in this post. Here they are in summary: This leads to the second reason I write: You. Much to my surprise, as I write, I find that there are others around the world who have similar questions and ideas as the ones I am having. As you have interacted with me on these posts and with this idea, I have learned from you, been taught and instructed by you, and have met many “kindred spirits” along the way. I consider many of you my “online friends.”

This leads to the second reason I write: You. Much to my surprise, as I write, I find that there are others around the world who have similar questions and ideas as the ones I am having. As you have interacted with me on these posts and with this idea, I have learned from you, been taught and instructed by you, and have met many “kindred spirits” along the way. I consider many of you my “online friends.”

I plan to release the eBook for FREE to subscribers of my blog newsletter near the end of this month. You can get a FREE copy of The Path of Freedom when it is released by

I plan to release the eBook for FREE to subscribers of my blog newsletter near the end of this month. You can get a FREE copy of The Path of Freedom when it is released by

But even more importantly, we must take note of the verbs God uses in Hosea 11:8 to describe what might happen to Ephraim and Israel if they do not turn from their ways. God says that they would be given up and handed over, just like Admah and Zeboiim. God says, “How can I give you up? … How can I hand you over?” It seems that according to Hosea 11:8, the destruction that came upon the four cities in the plain was not directly by the hand of God, but was because the people departed from the protective hand of God, and brought their destruction upon themselves.

But even more importantly, we must take note of the verbs God uses in Hosea 11:8 to describe what might happen to Ephraim and Israel if they do not turn from their ways. God says that they would be given up and handed over, just like Admah and Zeboiim. God says, “How can I give you up? … How can I hand you over?” It seems that according to Hosea 11:8, the destruction that came upon the four cities in the plain was not directly by the hand of God, but was because the people departed from the protective hand of God, and brought their destruction upon themselves.

The visitors strike the crowd with blindness, and tell Lot to flee the city with his family because “the Lord has sent us to destroy it” (Genesis 19:13). Lot pled with his two sons-in-law, but they would not flee, and ultimately, Lot was forced to flee the city with only his wife and two daughters.

The visitors strike the crowd with blindness, and tell Lot to flee the city with his family because “the Lord has sent us to destroy it” (Genesis 19:13). Lot pled with his two sons-in-law, but they would not flee, and ultimately, Lot was forced to flee the city with only his wife and two daughters.