Walter Kaiser has written a new book on the tough questions about God and His Actions in the Old Testament.

The questions Kaiser addresses in this book are all excellent questions. The answers he provides, however, are not.

Below is a list of the questions Walter Kaiser raises in his book, with a brief summary of his answers and a short statement about why I think his answers are wrong. The primary problem with all of Kaiser’s answers, however, is that he poses false dichotomies. I will try to point some of these out.

1. The God of Mercy or the God of Wrath?

Kaiser’s answer is “both” We cannot go to one extreme or the other. Kaiser understands God’s wrath as an act of love against sin which hurts those He loves. He also says that wrath is always preceded by love, grace, and mercy (p. 25).

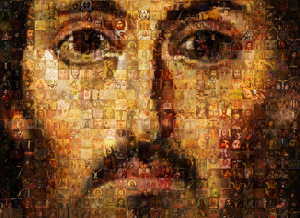

Kaiser’s big mistake is his flat-out rejection of the revelation about God in Jesus Christ. He does not agree with those who seek to understand the nature and character of God by looking primarily to Jesus. In the introduction to the book, he called this “Christo-exclusivism” (p. 11).

But again, if Jesus claims to reveal God to us (John 1:14, 18; 14:9-11; 2 Cor 4:4; Php 2:6; Col 1:15; Heb 1:2-3), then why would we ever reject the perfect revelation of God in Jesus Christ as the lens by which we understand the actions of God in the Old Testament? Kaiser’s rejection of the revelation of Jesus as an interpretive grid for the Old Testament almost caused me to stop reading the rest of his book.

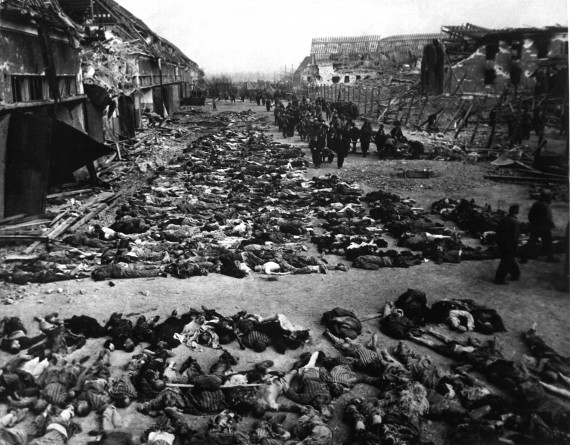

2. The God of Peace or the God of Ethnic Cleansing

Kaiser’s answer is that God did command the Israelites to practice genocide against the Canaanites, but this is only because the Canaanites were so evil (p. 29-30). Really, God was doing the whole world a favor by wiping such evil people off the face of the earth.

This is such a tired old answer, I had trouble believing Kaiser was still using it. Any student of history or literature knows that all the arguments used to defend the genocidal slaughter of one’s enemies are the exact same arguments we find in the Bible about why the Israelites went to war with the Canaanites. And we cannot say that “It was okay for the Israelites … because it’s in the Bible.” That won’t fly for anybody except the most close-minded of Christians.

Oh, and Kaiser says that this is WAY different than Jihad, or Holy War, of the Muslims. Why? Because God commanded His wars, whereas Jihad is only commanded in the Qur’an (p. 44). All I can say to that is … What?

3. The God of Truth or the God of Deception

Kaiser looks at some passages in the Bible where it appears that God deceives others (e.g., 1 Kings 22). Kaiser gets around these passages by providing the definition of a “lie” as intentionally speaking an untruth to people who deserve to know the truth with the intent of hiding the truth from them (p. 52).

Based on this, Kaiser says that God’s deceptions in the Bible are not really “lies” because the people who are deceived didn’t deserve to know the truth, and God didn’t really intend to lie to them anyway.

Again … what? If you are a parent, would you allow this sort of an explanation from your child about why they lied to you? I sure hope not.

4. The God of Evolution or the God of Creation?

Since I am currently doing a Podcast on Genesis 1, I was eager to read what Kaiser wrote.

But his explanation was quite confusing. As far as I could tell, he thinks that Genesis 1 should be understood scientifically, but not too scientifically. It didn’t happen millions of billions of years ago, but at the same time, a “day” isn’t really a 24-hour day (p. 65) and the only real point of the creation account is to tell us that God made mankind in His image (p. 70).

I also got somewhat upset when he rejected out of hand the idea that Moses was writing a polemic against the religions of his day. He said that this sort of idea has been “thoroughly discredited” (p. 63). I find this funny, because most of the scholars I have read in my own research and study do not share Kaiser’s opinion.

I also got somewhat upset when he rejected out of hand the idea that Moses was writing a polemic against the religions of his day. He said that this sort of idea has been “thoroughly discredited” (p. 63). I find this funny, because most of the scholars I have read in my own research and study do not share Kaiser’s opinion.

Overall, I found this chapter highly confusing and unconvincing. After reading it twice, I still was not sure what Kaiser was saying.

5. The God of Grace or the God of Law?

Kaiser’s answer is “God is both!” He uses the “Threefold division of the law” argument to make his case (p. 80) that while Christians should still follow the moral law, while rejecting the others.

But Kaiser knows that this arbitrary divisions of the law is not found within the Bible itself, but is forced upon the text by some scholars who want to keep some portions of the law, but not others.

6. The God of Monogamy or the God of Polygamy?

Kaiser’s answer is that while there are numerous examples of polygamy being practiced in the Bible, the clear New Testament teaching is that polygamy was a sin (p. 102).

I find this approach highly interesting, since earlier, Kaiser said that scholars should not allow the New Testament to guide or direct their understanding of Old Testament texts. I happen to agree with Kaiser, but I find it interesting that he appeals to the New Testament when it suits him.

7. The God Who Rules Satan or the God Who Battles Satan?

Kaiser argues that God created Satan to be good, but Satan rebelled and so God expelled Satan from heaven (p. 116). God allows Satan to continue to exist, just as God allows all of us rebellious sinners to exist.

I really don’t disagree too much with what Kaiser writes in this chapter, though I would have nuanced everything quite differently.

8. The God Who is Omniscient or the God who Doesn’t Know the Future?

Kaiser’s opinion is that God obviously knows everything, and that all the verses in the Bible which seem to indicate otherwise are nothing but anthropomorphisms (speaking about God in human terms).

Kaiser’s problem here is that he has created a false dichotomy. From a philosophical perspective, there are numerous other options, including middle knowledge, and knowledge of counterfactuals, and even the omniscient knowledge of all possible future events without knowledge of which future event will actually occur. In that last case, is it omniscience or is it not? I say yes.

9. The God who Elevates Women or the God Who Devalues Women?

This may be the best chapter in the book. Kaiser believes that all ministries and gifts are for all people in the family of God, both men and women included (p. 154).

I agree with Kaiser on this, so there is no objection from me.

10. The God of Freedom with Food or the God of Forbidden Food?

Apparently, Kaiser believes we still cannot eat pork or shellfish. According to Kaiser, all the Old Testament food laws are still to be followed today. Why? Because the prescribed foods are healthier, and the forbidden foods are unhealthy (p. 169).

Again, as with much of the rest of the book, I was shocked to read Kaiser’s answers and the logic he used to arrive at those answers. He completely negated everything taught by Jesus, Peter, and Paul about all foods being clean, permitted, and allowed.

Again, as with much of the rest of the book, I was shocked to read Kaiser’s answers and the logic he used to arrive at those answers. He completely negated everything taught by Jesus, Peter, and Paul about all foods being clean, permitted, and allowed.

Conclusion

I cannot recommend this book to anyone. Though the chapter on how God values women was worthwhile reading, the damage done by every other chapter in the book to the Gospel, to the character of God, and to the witness of the church in this world makes this book not worth reading.

The saddest thing of all is in the introduction to the book, Kaiser recognizes that the vast majority of those in their 20s and 30s are “the non-attenders at church and the non-religious” (p. 10). Kaiser thinks this is a bad thing (I think it is good), but what Kaiser fails to understand is that it is exactly the kind of theology he presents in this book which has caused most of those people to leave the church and give up on God.

Until our understanding of Scripture and our explanation of theology (and how we live out both in the world) are brought into conformity to Jesus Christ, people of all ages will continue to reject (and rightfully so) the teachings and theology of the church.

But I also knew that knowing Scripture, and knowing theology, and knowing about grace is not really the point of it all. The point of it all is to actually

But I also knew that knowing Scripture, and knowing theology, and knowing about grace is not really the point of it all. The point of it all is to actually

And trust me … if you follow Jesus, you will never get bored.

And trust me … if you follow Jesus, you will never get bored.

This is not about the sanctity of God’s Word, but about the sanctity of God’s people … namely, ALL people.

This is not about the sanctity of God’s Word, but about the sanctity of God’s people … namely, ALL people.

They are so scared, they cannot eat, they cannot sleep, they cannot think. They tell me about physical problems, emotional problems, relational problems, and all sorts of other problems they are experiencing because they are so afraid that God is out to get them because of something bad they said or thought about God.

They are so scared, they cannot eat, they cannot sleep, they cannot think. They tell me about physical problems, emotional problems, relational problems, and all sorts of other problems they are experiencing because they are so afraid that God is out to get them because of something bad they said or thought about God.

I was recently having a discussion with an atheist who had grown up in a Christian family and had gone to church for the first twenty years of her life. But she became an atheist in her 20s.

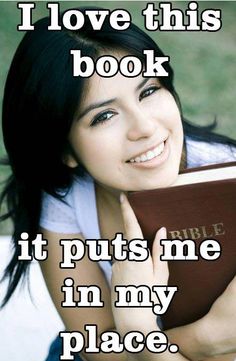

I was recently having a discussion with an atheist who had grown up in a Christian family and had gone to church for the first twenty years of her life. But she became an atheist in her 20s. So if you are a slave, and your master beats you harshly, the slave should just accept it. After all, fear of your master is a good thing.

So if you are a slave, and your master beats you harshly, the slave should just accept it. After all, fear of your master is a good thing.

But try to picture the scene. Was this like baby piñata day?

But try to picture the scene. Was this like baby piñata day?